Dramatic Vocalise Database

Gustav Holst (1874–1934)

The Planets, Op. 32 (1914–16)

1914, the year of Skryabin’s Prometheus and Ravel’s Daphnis in London, was also the year Gustav Holst began work on his suite for large orchestra, The Planets.

According to Raymond Head, the year Holst began looking at astrology “fairly closely,” the theosophist Alan Leo published The Art of Synthesis (1912), an innovative astrological book, which also includes an “Astro-Theosophical Glossary.” 1 Head believes that it is this book that inspired the composition of The Planets.

Unlike in all his previous books, Leo devoted a chapter to each planet, elucidating their special qualities and characteristics. Each chapter was given a heading: thus “Mars the Energiser,” “Venus the Unifier,” etc. This is the very manner that Holst adopted in The Planets. Indeed Holst’s title for the last movement, “Neptune the Mystic,” is exactly the same as Leo’s chapter-heading. Further examination of the book gives valuable ideas about what Holst thought of his planets and how this is represented in the music.2

According to his own “List of Compositions,” in a small notebook with a page for every year from 1895 to 1933, Holst wrote Mars, Venus, and Jupiter in 1914; Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune in 1915; and Mercury in 1916.3

By 1917, the full score of The Planets was finished. The work had to wait until the following year for a performance. According to Richard Greene:

In September of 1918, already having begun work on The Hymn of Jesus, Holst received the gift of a performance of his suite from his old friend, Balfour Gardiner. . . . With the prospect of a run-through of his composition, the strain of uncertainty was replaced with excitement and purpose, and Holst put his friends and pupils to work preparing a full set of parts for the performance. The choir of St. Paul’s Girls’ School was trained as the chorus for Neptune, and . . . after an hour of rehearsal, the first performance of The Planets took place.4

On 22 September 1918, a mere week before the premiere, Holst wrote to his friend Edwin Evans, saying:

My “Planet” pieces are to be done at Queen’s Hall next Sunday morning Sep 29 10.30 to 1.30. From 12.15 to 1.30 will be the best time. Boult is conducting. It will be a purely private affair but please tell anyone who you think would care to come. Entrance at orch door.5

The first full public performance of The Planets was performed at Queen’s Hall by the London Symphony Orchestra, under Albert Coates, on 15 November 1920.6

A connection between theosophy, Holst, and Skryabin’s Prometheus was not lost on Holst’s and Vaughan Williams’s friend and music reviewer Edwin Evans:

This monumental suite, “The Planets,” is to be judged solely as music. Like the theosophy of some of Scriabin’s later works, Holst’s astrology, whilst supplying a poetic basis, does not need to be accepted by the listener for him to appreciate the musical inspiration derived from it. I have long been of the opinion that the elaborate programme of “Prometheus” is an obstacle to its appreciation as music. “The Planets” is in no such danger, because the programme, instead of being elaborate, is extremely simple. The generally accepted astrological associations of the various planets are a sufficient clue in themselves to the imagination. . . . It is . . . unfamiliar to hail “Neptune,” the sea god, as a mystic, and “Uranus” as a magician; but once these relations are established in the titles of the movements, it is easy to fall into the mood of the respective tone-poems.7

The Planets includes wordless chorus in the final movement “Neptune, The Mystic.” Holst’s approach to such a chorus is new, for “Neptune” is the first strictly orchestral work that uses a “hidden” chorus. Hidden offstage chorus has been central to the idea of dramatic vocalization since its early appearance in Weber’s Der Freischütz onward, yet this was the first time the technique was applied to a symphonic and specifically non-dramatic context, not a ballet, nor opera.

When the chorus enters at the end of this final movement, the voices double instruments for quite some time. As the instruments slowly fade away the voices move into the foreground. Finally, they are left alone, a cappella, fading away into the distance.

Holst provides the following score direction on the first page of the movement itself:

The chorus is to be placed in an adjoining room, the door of which is to be left open until the last bar of the piece, when it is to be slowly and silently closed. The Chorus, the door, and any Sub-Conductors that may be found necessary are to be well screened from the audience.8

Adrian Boult commented on these score directions, stating:

I always regret that the precise directions which appear at the opening of “Neptune” as to the management of the hidden choir have not been shown also at the opening of the whole work.9

Holst’s daughter Imogen provides additional anecdotal information as to the use of the chorus in performances of “Neptune”:

In his live performances he [Holst] achieved a magical effect. He was very careful about placing the hidden semichorus so as to get the right sound. At the end of the movement, his idea of asking the singers to walk further away was the result of an experiment he tried in 1905 when he wrote a part-song with an echo-chorus for his singing-class at James Allen’s Girls’ School. An ex-pupil has described the performance, saying: “I remember the choir singing and walking off along a corridor and shutting themselves in a far-off room getting softer and softer—leaving the audience straining their ears for the last note.” Whenever Holst was going to conduct Neptune he always made his singers practice walking away while they sang their last repeated bar. On one occasion he asked me to play the cues for him at a chorus rehearsal in the Albert Hall, and I was able to see how he did it. After three repetitions of the last bar the singers slowly turned round and walked along a corridor, watching the beat of a sub-conductor, who led them into a room where the door was open to receive them. They walked the length of this room, still singing, while someone gradually closed the door, and at the performance they were able to go on singing until the audience’s applause told them that their voices were no longer audible. Holst made them rehearse this over and over again; any shoes that squeaked had to be taken off, and the door had to be shut absolutely silently. And he implored them to control their breathing so that nothing would interrupt the legato of that diminuendo.” 10

Adrian Boult, conductor of the premiere, added to this information:

I should perhaps here point out that the composer sanctioned a modification of the instruction to close the door separating the chorus from the hall. This was in Canterbury Cathedral, when we had the choir in the triforium, where there were no doors, and so we made the choir itself move into the distance until it could be heard no longer. I usually now adopt this practice in concert halls. It is more difficult for the singers, but much more effective.11

The manuscript score fails to contain a vowel for the chorus. Imogen Holst gives the following clue as to the proper choice:

In 1971, when Faber Music Ltd asked me to revise the Chorus part of Neptune for reprinting, I realized that the singers had never been given a written vowel sound, either in the score or in the part. Knowing the sound that Holst had wanted at his rehearsals, I added the same instruction he had written for the hidden choir in Savitri: “Sing throughout to the sound of ‘u’ in ‘sun.’” 12

Reviews of The Planets were mixed. Ernest Newman gave praise in his Sunday Times review of the first full public performance of the work:

The vocal finale of Neptune is at once one of the most daring pieces of modern writing and one of the most effective.13

Likewise, Alfred Kalisch recognized the importance of the wordless chorus in his review published by the Musical Times:

The concert was memorable for the first complete performance of Mr. Gustav Holst’s “The Planets.” It would be superfluous again to discuss this very remarkable work in detail. It is a good testimonial to the taste of the public that at each repetition it is received with greater enthusiasm. The whole gains immensely when rounded off by the last number, “Neptune the Mystic” (heard for the first time), with its ethereal ending, which presents almost super-human difficulty to the female chorus.14

Yet not all of London was so easily impressed. An anonymous reviewer from The Sackbut eloquently expressed his reservations:

The whole work gives one the impression of being an anthology of musical platitudes laboriously compiled from the pages of nearly all the prominent modern composers. . . . In “Neptune” we were treated to a bevy of Debussy’s sirens signaling theatrically from the organloft. Even after they had gone out, shutting the door behind them with an audible click, they continued to exhale their colorless melismata through the keyhole. These may seem hard words, but one cannot stand by unmoved while a perfectly inoffensive and, on the whole, well-meaning cosmos is butchered to make a policeman’s holiday.15

Richard Greene likewise highlights Holst’s debt to French music in his assessment of “Neptune”:

The psychological program behind each movement of The Planets is activated by the same metaphoric action as found in a work such as Nocturnes, for the two composers appear to work from the same rhetorical principles. Debussy based his work on the French Symbolist movement which was heavily influenced by the techniques of musical character practiced by Wagner. And it is through Wagner, as common ancestor, that Holst’s debt to the composer of the Nocturnes can be understood.16

The novelty of Holst’s use of dramatic vocalization in The Planets was not lost on his friend and colleague Vaughan Williams. In a two-part article on Holst in Music & Letters in 1920, a few months before the first full public performance of The Planets, Vaughan Williams wrote the following:

Such a work as “Neptune” (the mystic) seems to give us such a glance into the future—it ends, so to speak, on a note of interrogation. Many composers have attempted this, sometimes bringing in the common chord at the end as an unwilling tribute to tradition, sometimes sophisticating it by the addition of one discordant note, sometimes letting the whole thin out into a single line of melody; but Holst in “Neptune” actually causes the music to fade away to nothing. We look into the future, but its secrets remain closed to us.17

The following year, 1921, Vaughan Williams composed a similar ending to his Pastoral Symphony.

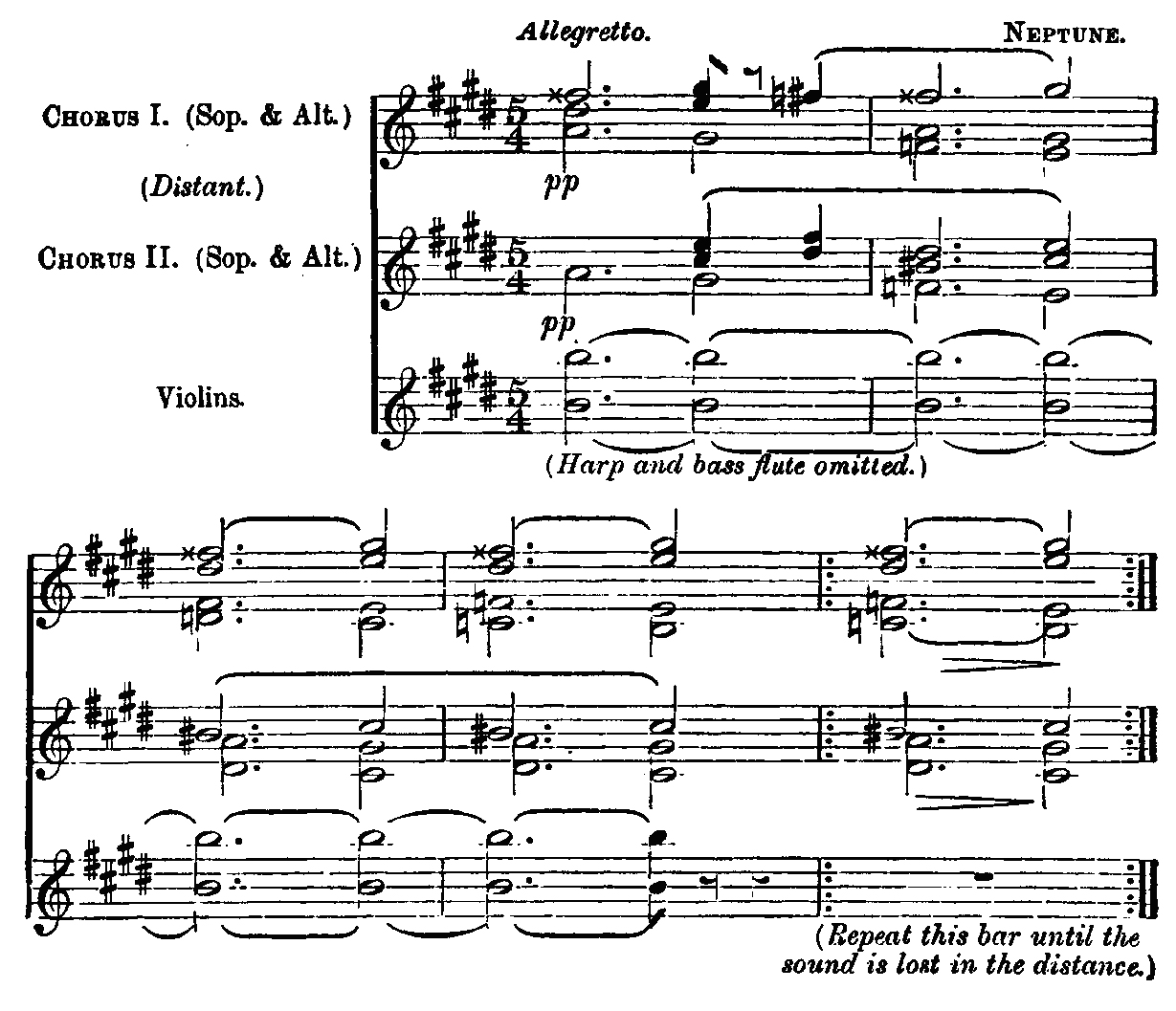

Holst, The Planets, “Neptune,” mm. 97–101

18(Nauman 2009, 158–64)

Examples | Comments |

| “Neptune” (complete) |

Footnotes

1 Raymond Head, “Holst—Astrology and Modernism in ‘The Planets,’” Tempo 187 (1993): 18.

2 Ibid.

3 Imogen Holst, introduction to The Planets, op. 32, by Gustav Holst, in Collected Facsimile Edition of Manuscripts of the Published Works, vol. 3 (London: Faber Music, 1979), 9.

4 Richard Greene, Holst: The Planets (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 28–29.

5 Ibid., 12.

6 Coates conducted the premiere of Delius’s The Song of the High Hills on 26 February 1920.

7 Edwin Evans, “Modern British Composers VI.—Gustav Holst (Concluded),” Musical Times 60 (1919): 659.

8 Gustav Holst, The Planets. (New York: Dover, 2000), 162.

9 Sir Adrian Boult, “Interpreting ‘The Planets,’” Musical Times 111 (1970): 263.

10 Imogen Holst, introduction to The Planets, op. 32, 13.

11 Sir Adrian Boult, “Interpreting ‘The Planets,’” 263.

12 Imogen Holst, introduction to The Planets, op. 32, 13.

13 Ernest Newman, The Sunday Times (21 November 1920); quoted in Greene, Holst: The Planets, 33.

14 Alfred Kalisch, “London Concerts,” Musical Times 61 (1920): 821.

15 Quoted in Richard Greene, Holst: The Planets, 36.

16 Ibid., 23.

17 Ralph Vaughan Williams, “Gustav Holst,” Music & Letters 1 (1920): 190.

18 Ibid.