Dramatic Vocalise Database

Gustav Holst (1874–1934)

Sāvitri, Op. 25 (1916)

During the first decade of the twentieth century Holst became interested in theosophy, as well as in Sanskrit literature. Vedic theogony appears shortly after in his Indian-themed works: Sita (begun in 1899 or 1900), Maya for violin and piano (1901), and Indra for full orchestra (1903). Holst followed up these works with the chamber opera Sāvitri (1908–9).

The unpublished three-act opera Sita (1900–6), based on the Ramayana, was awarded Third Prize in the Ricordi competition in 1908; the work was never performed. A passage in act 1 includes the use of an offstage chorus of “voices of the earth . . . to be placed so far away that only a faint murmur is heard by the audience.” 1 This example of dramatic vocalization predates Vaughan Williams’s studies with Ravel, performances of Delius, and Debussy’s “Sirènes” in London.

The chamber opera Sāvitri was started in 1908 and completed on 27 April 1909. Holst wrote his own libretto, founded on a story from the Mahabharata. According to Edwin Evans:

The substance of the story is simple, but lends itself admirably to dramatic treatment. Savitri hears the voice of Death announcing that he comes to claim her husband, but her piety obtains a boon on condition that she asks nothing on his behalf. She pleads for life in its fullness. That being granted, she declares that the gate of life can only be opened for her by Satyavan, her husband, and her wifely devotion is rewarded.2

In the score Holst includes a note regarding the orchestration and performance of this piece:

This piece is intended for performance in the open air, or else in a small building. When performed out of doors there should be a long avenue or path through a wood in the centre of the scene. When a Curtain is used, it should be raised before the voice of Death is heard. No Curtain, however, is necessary. The Orchestra consists of two string quartets, a contra-bass, two flutes, and an English Horn. There is also a hidden chorus of female voices. They are to sing throughout to the sound of “u” in “sun.” Conductor, Chorus, and Orchestra are to be invisible to the Audience.3

The women’s chorus was originally written as SATB but altered at the suggestion of Hermann Grunebaum, conductor of the first private performance on 5 December 1916 at the London School of Opera, Wellington Hall, St. John’s Wood. The first public performance was on 23 June 1921 at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith, conducted by Arthur Bliss.

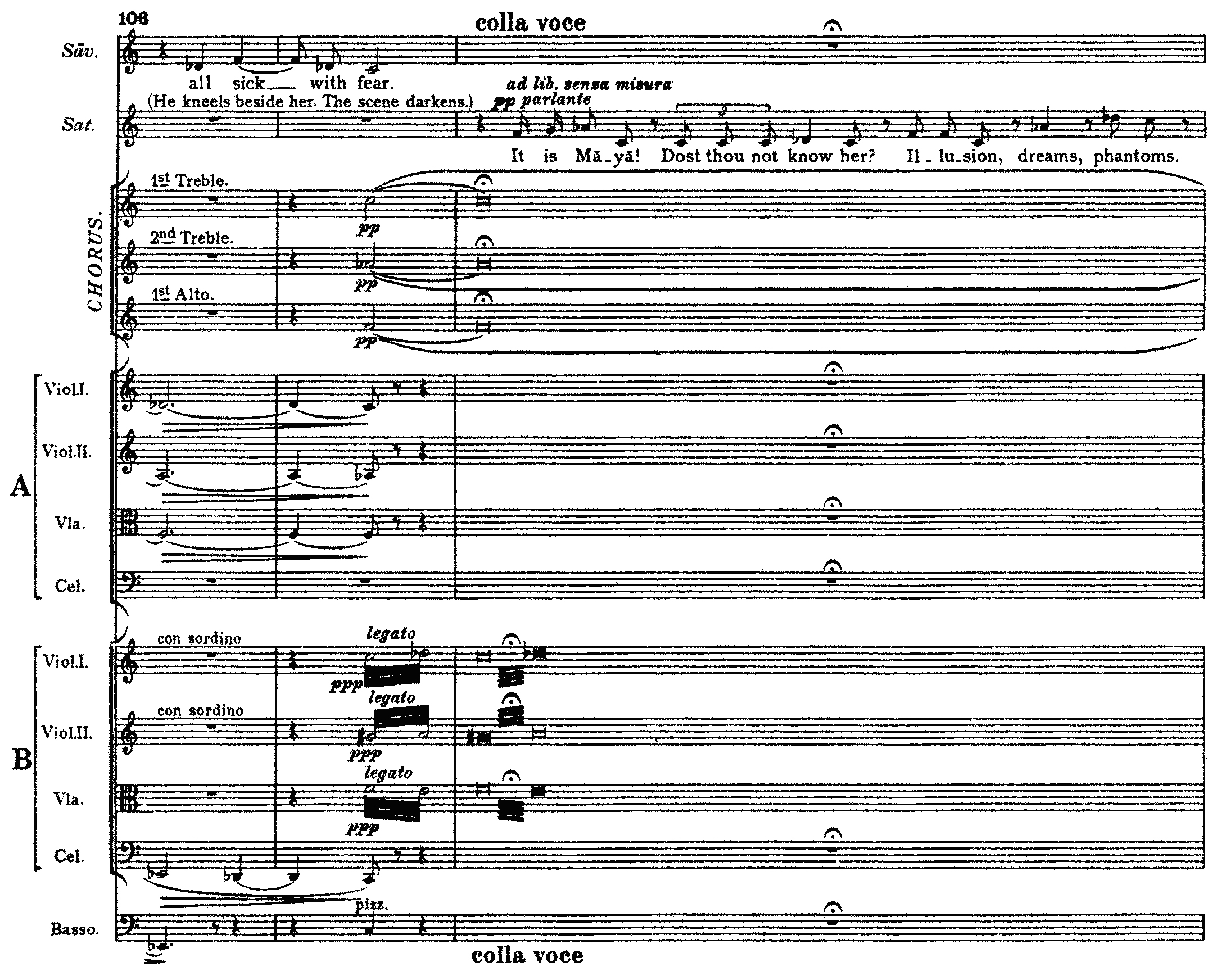

The “invisible” chorus adds to the overall mystical effect during three separate episodes in the opera. When Satyavan sings of maya—illusion—his voice is set against the remote sound of the hidden chorus. According to Colin Matthews, their voices symbolize “the divine world interacting with the mortal.” 4

Holst, Sāvitri, mm. 106–8

5Dramatic vocalization again occurs when Death reappears to claim Satyavan.

Holst, Sāvitri, mm. 214–19

6The wordless chorus finally joins with Savitri as she rejoices in her victory over Death, who has yielded to Savitri’s plea that her life cannot be complete without Satyavan.

A review by John Brande Trend of the premiere highlights the importance of the hidden chorus in this opera:

At the performances at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith, and at the Royal College of Music, there was no attempt at local color, or at superficial Indian effects; yet the atmosphere seemed strange and remote, and the thought (to those of the audience who had never been in India) seemed thoroughly in keeping with what they imagined Sanskrit literature to be.

The mood of the piece was set by the singing behind the scenes of three of Mr. Holst’s Choral Hymns from the Rig-Veda. When the hymns had been sung (the words were Mr. Holst’s own translation, and the performers a choir of women’s voices and harp), it seemed perfectly natural to hear the unaccompanied voice of Mr. Clive Carey, as Death, announcing to Savitri from behind the scenes that he had come to claim her husband. Savitri (Miss Dorothy Silk) answered in the same manner;

and it was as if a word or two of speech slid naturally into unaccompanied singing and a melody which in itself was expressive enough and clear enough to be adequate to all the needs of the dramatic situation. From the beginning, the task of expression lay with the voices. The orchestra behind the scenes was limited to two string quartets, a double bass, two flutes, and English horn, and the choir of female voices. It was nearly always subsidiary and kept well in the background; on the rare occasions when it was used to support a passionate climax (such as the scene between Savitri and Death) it was hardly so successful.7

In this opera the chorus is instructed to remain hidden from the audience’s view; its contributions are kept to a wordless vocalization, its use only occurs at the mention of maya—illusion—or the appearance of the supernatural character of Death. It is not insignificant that Holst would make an association with maya and its “otherworldly” depiction by means of wordless vocalization.

(Nauman 2009, 146–51)

Examples | Comments |