Dramatic Vocalise Database

Frederick Delius (1862–1934)

The Song of the High Hills (1911)

Throughout his career, Delius maintained a strong attachment to the mountain ranges of Norway due to his friendship with Edvard Grieg. His desire to express in music images of their grandeur and beauty is evident in his earliest surviving work, the song “Over the Mountains High” (1885). His attraction to Norwegian scenery and the cultural life of the country was at its greatest intensity during the decade from 1888 to 1898. To these years belong Delius’s three early large-scale mountain-scapes: the melodrama Paa Vidderne (1888), a symphonic poem with the same name (1890–92), and the “fantasy overture” Over the Hills and Far Away (1895–97). His last mountain-themed work was The Song of the High Hills (1911) for mixed chorus and large orchestra.

The Song of the High Hills is one of Delius’s greatest works, a symphony wherein the choir is used as a second, distant ensemble. Of his score, Delius wrote in the program notes for the premiere:

I have tried to express the joy and exhilaration one feels in the mountains, and also the loneliness and melancholy of the high solitudes and the grandeur of the wide, far distances. The voices represent Man in Nature, an episode which becomes fainter and then disappears.1

The chorus in this work sings no words; pure vocalization is employed as a means of poetic evocation. In the original score he gives the direction, “The chorus must be sung on the vowel which will produce the richest tone possible.” 2 Occasionally, a solo tenor voice seems to detach itself from the tonal fabric as a whole, but imperceptibly it disappears once more into the disembodied sound from whence it came.

The Song of the High Hills has the most individual form of any textless work by Delius. It is ternary in outline, with an expansive interlude in the first section that foreshadows the intense contemplation of the central portion of the work. There is a strongly marked point of recapitulation and more obvious repetition of material. Two principal elements constitute the structure: opening and closing sections of forceful, striving material, and a central sequence of serene episodes based on a lovely, Grieg-like melody.

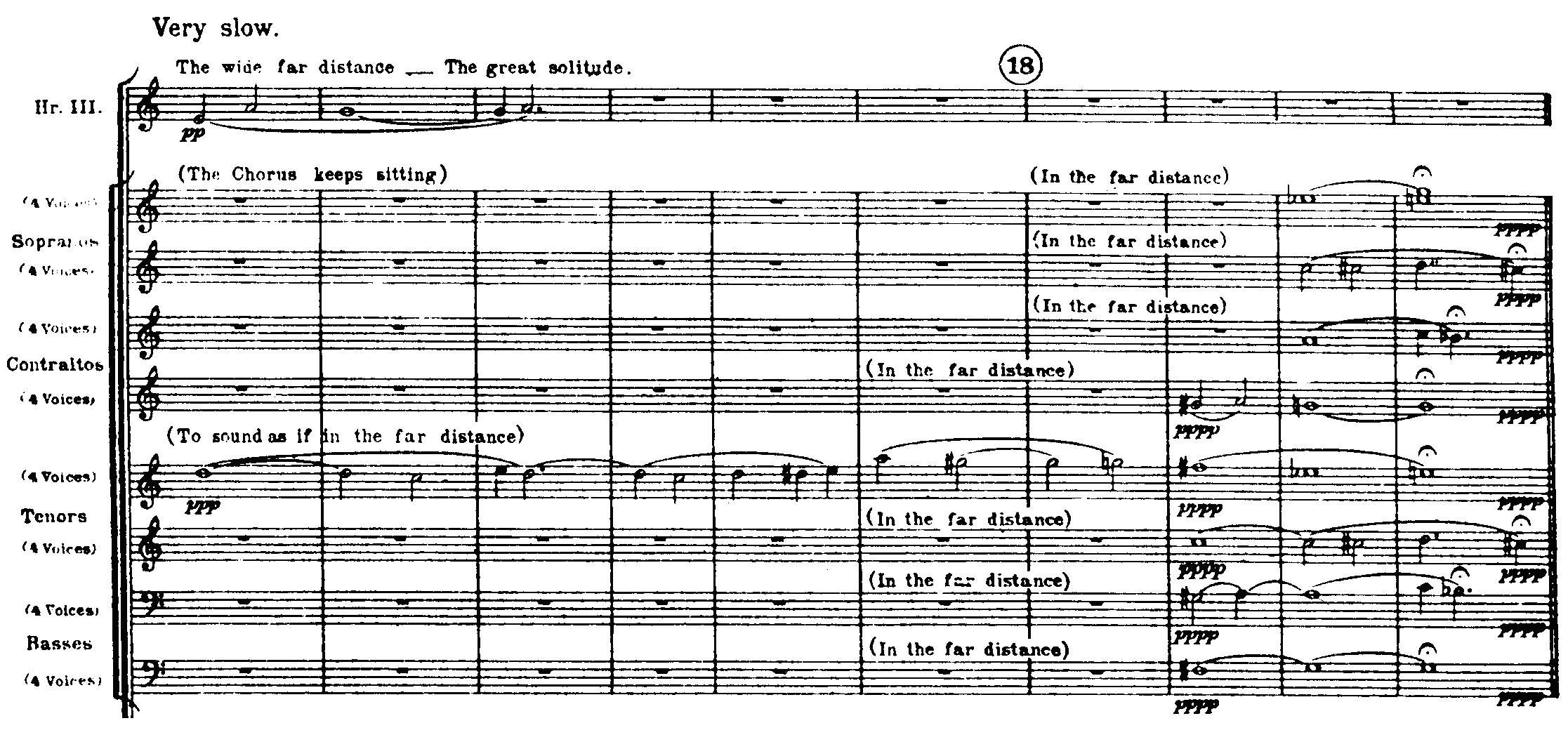

Delius, The Song of the High Hills, mm. 164–71

3According to Andrew Boyle:

The outer portions are daring and striking in their unprecedentedly bleak but fresh harmonies, and harsh orchestral color and weight, but they are but necessary rites attending on the celebration of nature which is the work’s core. Here, in extended episodes of repeating calls, the piece seems to move outside time altogether, to a sphere of contemplation. The harmony suggests no real point-of-rest, nor any sense of pace of continuity, with the constant ostinato of the calls overlying a permanent shifting tonal centre. A short review of the striving style of the opening lifts the central section onto a seemingly higher plateau, where the distant murmurs of wordless chorus accompany the entry of the work’s main theme. The ethereal mystery of the wordless vocal texture, whether in a single disembodied voice or in the last mighty statement of the mountain-hymn, seems to utter the timeless solitude of an unworldly wilderness. And in this great climax of voices at the end of the central “plateau” one can sense that, rather than there being more volume or more parts added, one is simply becoming better attuned to the countless sounds that are eternally singing in nature. At the piece’s final dying dissonance, also, there is no resolution or any real end to the voices’ sounding, only a fading of our ability to hear them.4

The chorus first enters as accompaniment to the main theme presented by the violins. Delius indicates that the chorus should remain seated, as in Appalachia. In addition, there is a note in the score at the moment of the chorus’s entry, “The wide far distance—The great solitude.”

Delius, The Song of the High Hills, mm. 164–73

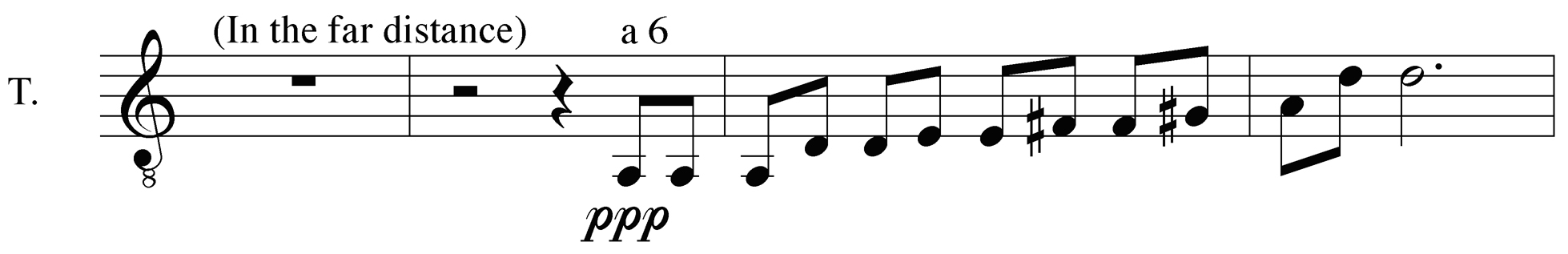

5Shortly afterward, the tenor section sings a brief wordless passage

.

Delius, The Song of the High Hills, mm. 200–203

This motive later appears in the full chorus, followed by an echo of the original melody in the first sopranos.

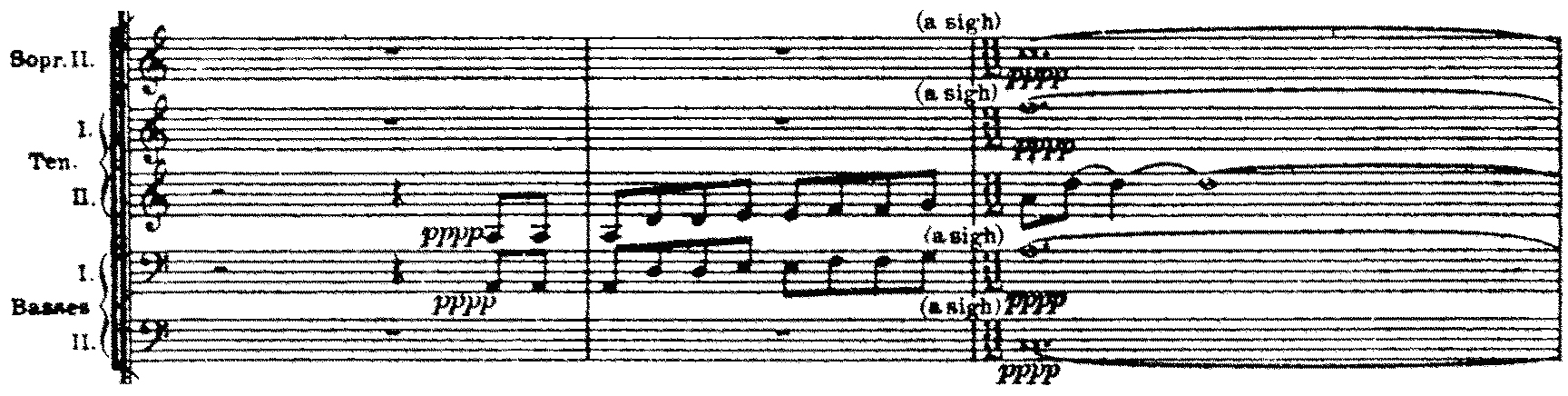

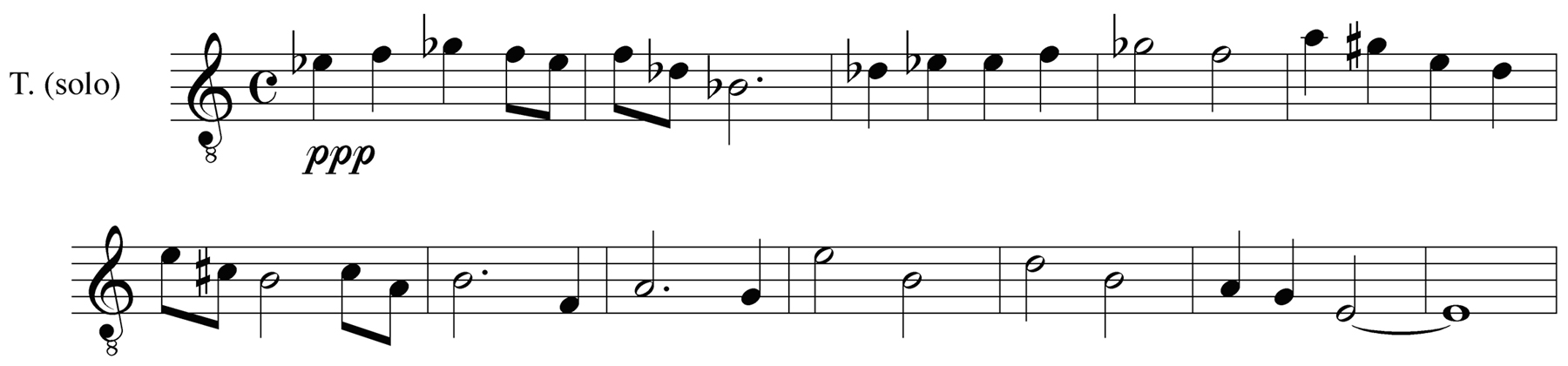

Delius, The Song of the High Hills, mm. 246–52

6A wordless solo tenor in the chorus then presents the main theme.

Delius, The Song of the High Hills, mm. 260–71

The full chorus then presents the theme in an a capella harmonization.

Delius, The Song of the High Hills, mm. 275–90

7At measure 288, solo soprano and tenor sing the ascending phrase from the tenor’s earlier entry as counterpoint to the main theme. The chorus proceeds unaccompanied for seventeen measures before the orchestra joins them, leading to a tremendous crescendo and climax. The voices steadily fade away to pppp. The orchestra builds to one last dynamic outburst, marked “With Exultation. not hurried” [sic] in the score before dying away in the strings, like the chorus before.

The Song of the High Hills is the consummate expression of Delius’s contemplative spirit and attachment to nature. In this work he achieved a blending of art and nature at its least transient and most profound. Although written before World War I, the work would have to wait until 1920 for a performance, when Albert Coates conducted the premiere at Queen’s Hall in London on 26 February.8

The review of the premiere by Alfred Kalisch points out for special recognition the a capella section referenced above.

Mr. Delius was the hero, too, of the Philharmonic Concert on February 26, when the new Philarmonic [sic] Choir, organized by Mr. Charles Kennedy Scott, sang for the first time his “Song of the High Hills,” which is a record of the composer’s impressions of Norwegian mountain solitudes on a balmy summer night. For a brief moment the voice of Man intrudes, but grows fainter and fainter. A part of the work is in Delius’s usual vein, but in the choral numbers he displays an amount of vigor unusual with him, and there is an unaccompanied section culminating in a massive climax which will probably be judged in future to be the strongest music he has ever composed. An interesting point about the work is that the chorus sings no words, but only varying vowel sounds.9

Harvey Grace, under the name “Feste,” offers a terse, similar view in the same volume:

Choir showed high musical intelligence in Delius—characteristic idiom—groping chromatics—vague tonality—beauty subtle and elusive; did not elude choir—seized it and passed it on to audience.10

W. McNaught added a third opinion to the April volume of the Musical Times:

Congratulations to Mr. C. Kennedy Scott and the Philharmonic Choir on their excellent start. The experience of hearing the full orchestral and choral rehearsal of Delius’s “Song of the high hills” was sufficient evidence that London’s new choir is destined to rank high. The precision with which it threaded its way through the harmonic maze of the unaccompanied music, and kept perfect intonation for the re-entry of the orchestra, was a notable technical feat. Not many choirs could be certain of doing this—perhaps even the Philharmonic Choir would not make a “bull’s-eye” every time. Incidentally, this is an example of unpractical—one might say unfair—writing on the composer’s part. There is always a tendency for unsupported voices to sing in the untempered scale, and when they make modulation after modulation, it is a mere matter of arithmetic that they will lose the original pitch. Perhaps in the continual balancing of error they will maintain or return to it. But when accompaniments are to be re-introduced after an unaccompanied passage, there is more to be gained than lost by doubling voice-parts unobtrusively by a few instruments. It can be done so that the impression of unaccompanied singing is not destroyed. However, the Philharmonic Choir made good without this help.11

In all three cases, however, the author fails to connect this work to others in the same vein, such as Holst’s The Planets, or Debussy’s “Sirènes.” Technical praise is lavished on the chorus, but the novelty of a seated textless chorus seems to be almost completely ignored.

(Nauman 2009, 130–37)

Examples | Comments |

| The Song of the High Hills, mm. 164–73 |

| The Song of the High Hills, mm. 194–204 |

| The Song of the High Hills, mm. 245–364 |

| The Song of the High Hills (complete) |

Footnotes

1 David Hall, liner notes to A Song of the High Hills, by Frederick Delius.

2 Frederick Delius, Brigg Fair and Other Favorite Orchestra Works (New York: Dover, 1997), 146.

3 Ibid., 167.

4 Andrew J. Boyle, “The Song of the High Hills,” Studia Musicologica Norvegica 8 (1982): 147.

5 Frederick Delius, Brigg Fair and Other Favorite Orchestra Works, 167.

6 Ibid., 176–77.

7 Ibid., 179–80.

8 Coates also conducted the first complete performance of Holst’s The Planets in 1920.

9 Alfred Kalisch, “London Concerts,” Musical Times 61 (1920): 247.

10 Harvey Grace [Feste, pseud.], “Interludes,” Musical Times 61 (1920): 241.

11 W. McNaught, “Choral Notes and News,” Musical Times 61 (1920): 253.