Dramatic Vocalise Database

Carl Maria von Weber (1786–1826)

Der Freischütz (1821)

With the rise of a growing and increasingly powerful middle class after 1820, a new kind of opera came into being. It was designed to appeal to the relatively uncultured audiences who thronged the opera theaters in search of excitement and entertainment. Supernatural elements, including dramatic vocalization, borrowed from popular “paratheatrical” entertainments such as phantasmagoria shows, were soon included.

As early as 1810, soon after the publication of the Gespensterbuch [Book of Ghosts] by August Apel and Friedrich Laun, Carl Maria von Weber’s friend Alexander von Dusch told him about one of the short stories it contained. The first story in the Gespensterbuch, “Der Freischütz,” was based on a tale that Apel had come upon when he was a student, in a collection from 1730 called Unterredungen von der Reiche der Geister [Conversations from the Realm of Spirits]. This story appealed particularly to him and Laun, since it turned on the possibility of spirits assuming earthly form and controlling the elements or making pacts with humans. In the story, a character, in order to profit by good marksmanship, agrees to join in a series of diabolical rituals so as to obtain bullets that will go where he chooses, so-called “Freikugeln” [“free bullets”]. When Apel and Laun worked this story up as the first of their own collection, the central figure is described by the story’s title as “Der Freischütz” [“The Freeshooter”], the marksman who uses such ghostly “free bullets.”

Although initially interested in composing an opera based on this tale—Weber produced a sketch of a scenario and a few scenes—it was not until October 1816 that he revisited the idea. Weber turned to Friedrich Kind, a minor writer who formed part of his Dresden circle, to write the libretto. By 1 March 1817, the entire text was ready.

The composition of Der Freischütz occupied Weber for an unusually long time. He wrote the first sketch on 2 July 1817, and did not complete the score until 13 May 1820. His official activities—conducting and composing for court festivities in Dresden—and other previous commitments did not permit him to work uninterruptedly, and practically nothing was done on the opera in all of 1818.

At the beginning of May 1821, Weber went to Berlin, where he immediately began rehearsals of his opera. The first performance took place on 18 June 1821, with the composer conducting. The audience included E. T. A. Hoffmann, Heinrich Heine, and the young Felix Mendelssohn.

Although the libretto of Der Freischütz is attributed to Kind, Anthony Newcomb suggests that Weber may have been responsible for the creation of the “Wolf’s Glen” scene, the act 2 finale.1 Weber reports discussing the opera at length with Kind during the ten-day period in which the libretto was written.2 On 26 March 1821, Weber wrote to Hinrich Lichtenstein in Berlin:

I can well believe that you can’t make heads or tails out of many things in Freischütz. There are things in it that have never been presented on the stage in this way—which I had therefore to create entirely out of my own imagination, without the slightest adherence to precedent.3

One of the clearest indications of Weber’s personal involvement in the design of the “Wolf’s Glen” scene is a sheet of directions, written in his own hand, apparently as a guide to the upcoming performance in Dresden.4

The most striking and novel aspect of the “Wolf’s Glen” scene is the inclusion of an offstage chorus, providing one of the first true instances of dramatic vocalization.5 The beginning of the scene is prefaced in the score by the following description:

Furchtbare Schlucht, grösstenheils mit Schwarzholz bewachsen, von

hohen Gebirgen umgeben. Von einem derselben stürzt ein Wasserfall. Der

Vollmond scheint bleich. Zwei Gewitter von entgegengesetzter Richtung

sind im Anzuge. Weiter vorwärts ein vom Blitz zerschmetterter, ganz

verdorrter Baum, inwendig faul, so dass er zu glimmen scheint. Auf der

andern Seite, auf einem knorrigen Aste eine grosse Eule, mit feurig

rädernden Augen. Auf andern Bäumen Raben und anderes Waldgevögel.6

[A fearsome forest gorge, thickly wooded with dark trees and encircled by

high mountains. On one side a waterfall plunges down. A full moon shines

with a sickly light. Two thunderstorms are approaching from opposite

directions. Slightly to one side stands a blasted oak, so dead that its rotting

core gives off a ghostly light. On the other side an owl with rings of fire

around its eyes squats on the gnarled branch of a tree. Ravens and other

birds of the forest sit in the other trees around.] 7

Weber’s music complements the above description by accompanying the stage action with unsettling tremolo violins and violas, doubled by clarinets, all in their lowest register. Somber trombone chords punctuate the beginning and end of the opening twelve-measure phrase. The cellos and basses enter in measure 2, followed by their chromatic descent to the leading tone (E#), before leaping down to the dominant (C#). The upper strings and clarinets share a similar descending chromatic contour.

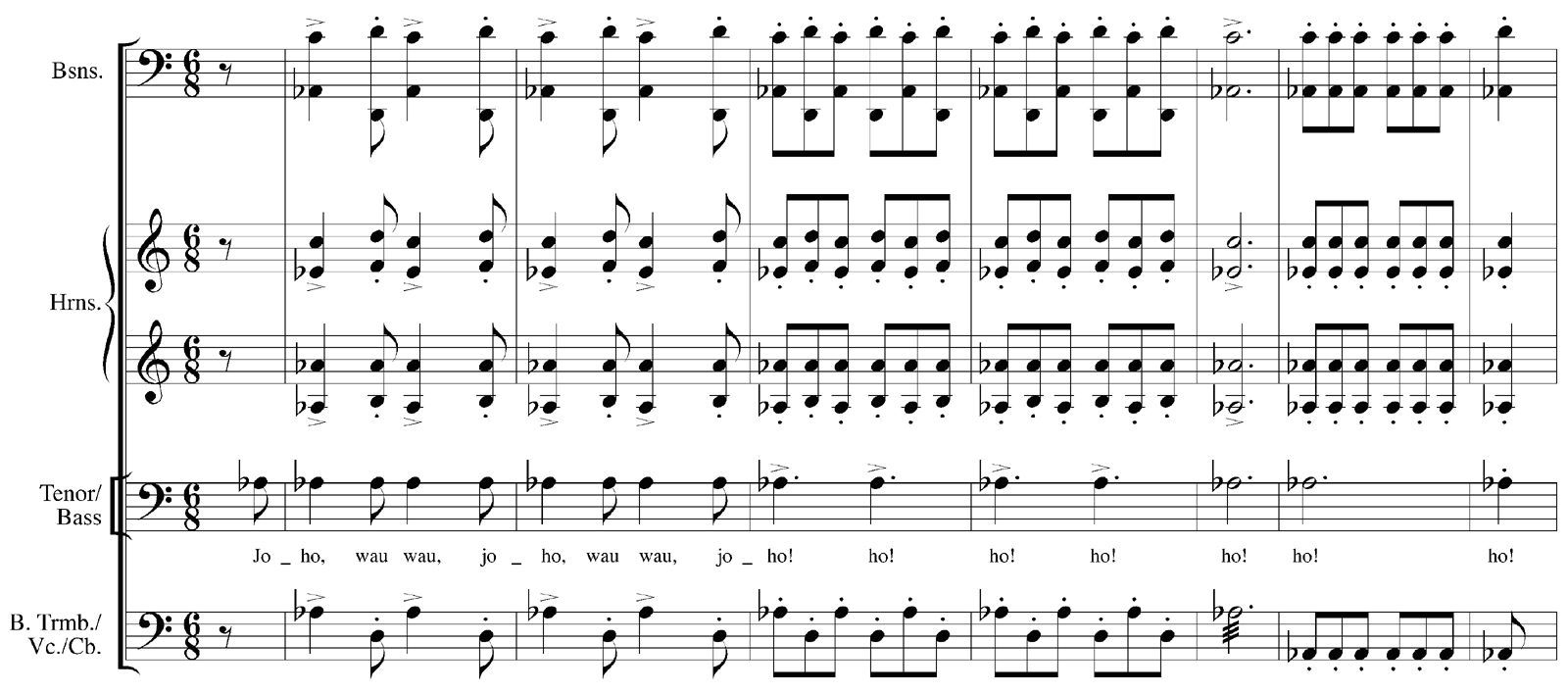

Weber, Der Freischütz, act 2 finale, “Wolf’s Glen” scene, mm. 1–16

The action is as follows:

Caspar (ohne Hut und Oberkleid, doch mit Jagdtasche und Hirschfänger,

ist beschäftigt, mit schwarzen Feldsteinen einen Kreis zu legen, in dessen

Mitte ein Todtenkopf liegt. Einige Schritte davon der abgehauene

Adlerflügel, Giesskelle und Kugelform.) 8

[Caspar (without hat or coat, but carrying a game bag and hunting knife, is

making a circle of black stones. In the middle of the circle is a skull, and a few

paces away lie the severed wing of an eagle, casting ladles, and bullet molds.)] 9

The first dissonant chord, a fully-diminished seventh chord in measure 4, coincides with a melodic leap of a tritone in the first violins. This pronounced leap, and more importantly, its intervallic content foretell of the diabolic events to come.

The overall effect of the orchestral opening is to produce a sinister and eerie mood. The introduction concludes with the entrance of the offstage “Unsichtbare Geister” [“Invisible Spirits”] intoning an incantatory chant (mm. 13–41). Weber indicates in the score: “Chor unsichtbarer Geister von verschiedenen Seiten” [“Choir of invisible spirits from different sides (of the stage)”].10

Milch des Mondes fiel aufs Kraut,

Uhui! Uhui!

Spinnweb ist mit Blut bethaut!

Uhui! Uhui!

Eh noch wieder Abend graut,

Uhui! Uhui!

ist sie todt, die zarte Braut!

Uhui! Uhui!

Eh’ noch wieder sinkt die Nacht,

ist das Opfer dargebracht.

Uhui! Uhui! Uhui! 11

[Moon-milk falling on the grass,

Oohooey! Oohooey!

Spider’s web with blood o’ercast!

Oohooey! Oohooey!

Before the evening shadow’s cast,

Oohooey! Oohooey!

the tender bride will die, alas!

Oohooey! Oohooey!

Before the owl has hooted thrice,

accomplished is the sacrifice!

Oohooey! Oohooey! Oohooey!]

The bass voices chant every line of text (“Milch des Mondes,” etc.) entirely on the tonic note, each phrase punctuated by a unison outburst “Uhui! Uhui!” in the upper three voices. The moment the upper voices enter, the cellos and basses leap up a tritone (F#–C), once again reinforcing the diabolic nature of the events.

The text of this magic spell foreshadows the accidental murder of Agathe at the hands of her beloved Max. Tricked by his fellow gamekeeper Caspar, who is secretly under an outstanding obligation for his soul to the demonic Samiel, Max has come to the Wolf’s Glen to assist in the forging of seven magic bullets. Max feels a lack of confidence in his ability to win a shooting contest, the prize being marriage to Agathe. So he agrees to the use of the bullets, which will supposedly hit their mark, but are in fact destined for Agathe.

Following the casting of the fifth magic bullet, the offstage chorus sings once more.

Weber, Der Freischütz, act 2 finale, “Wolf’s Glen” scene, mm. 365–71

Once again the text is accompanied by the interval of a tritone (Ab–D). These are the only sections in the entire opera containing “invisible spirits” or offstage chorus and, as such, have particular interest and importance for this study.

The entire scene easily divides into a series of smaller segments. Each of these sub-units is further divided by sudden shifts in tempo and meter, and alternate between recitative, spoken melodrama, and lyrical arioso passages. The scene’s unexpected nature and unpredictable means offer a clear contrast to the regularity of much of the rest of the opera, thus further highlighting its unique aspects.

E. T. A. Hoffmann’s creative work and last illness did not permit him the time to produce the review of Der Freischütz that he had assured his friend Weber he would write. Weber wrote to his librettist Kind on 21 June 1821, “I am still anxious to hear what Hoffmann had to say.” 12 On 9 August 1821, Weber also wrote to Friederike Koch, “Hoffmann wanted to write about the Freischütz, but appears to have forgotten it. My friend Wollank could perhaps remind him of it, and also himself at the same time.” 13

Hoffmann’s long-supposed authorship of a famous series of reviews of the Berlin premiere of Der Freischütz was brought into question in 1957 by Wolfgang Kron.14 His evidence shows that Weber clearly did not think Hoffmann had written the reviews, and that whoever wrote them wrote as if he were a frequent reviewer for the Vossische Zeitung at the time, which Hoffmann was not. Since the evidence for Hoffmann’s authorship seems to be only a suggestion made forty years after the fact by Julius Benedict, a pupil of Weber, the case for his actually having written the reviews seems doubtful.

These reviews are critical not mainly of Weber’s music, which the reviewer calls the best since Mozart and Fidelio, but of the current theater’s fascination with demons, hellish horrors, and invocations of the devil. About the “Wolf’s Glen” scene he says that it is a great display piece for the scene designer and the Maschinisten. As a result, he says, there is too much distraction for the eye, and the ear can scarcely follow the “düsterwilden Musikstücken” [“wild and gloomy music”]. He says he cannot fathom the Composer’s intentions in this scene: “a musical scene like this has never and nowhere been written.” His reaction to the music, then, is more puzzlement than rejection; it is the style of the staging that he objects to.

This sentiment echoes similar thoughts presented in an earlier letter from Goethe to Schiller on 23 December 1797:

You will have heard a hundred times that, after reading a good story, one wished to see it represented on the stage. And how many bad plays have come into being thus! Similarly people want to see every interesting situation engraved in copper, so that no active role is left for their imagination. So everything should be real to the senses, completely present, dramatic—and this “dramatic” itself should completely overshadow the really true. The artist should resist these thoroughly childish, barbaric, tasteless tendencies with all his might.15

Goethe was expressing his distaste of elements from popular entertainments being used in “true” theater. These entertainments, which Anthony Newcomb calls “paratheatrical,” “arose out of the intersection in the entrepreneurial market of burgeoning technology, fostered by science and the Industrial Revolution, and the insatiable appetite for diversion of the growing urban middle class.” 16

As Goethe remarks above, the tastes that went with this appetite were not always the most sophisticated. The most striking instances—balloon rides, Madame Tussaud’s wax gallery, the panorama, the phantasmagoria—were not considered high art. Nonetheless, they were popular and commercially lucrative; they fascinated the contemporary public and press; and their descendants survive in amusement parks and the movie industry. Newcomb proposes these phantasmagoria to be the source of many distinctive elements in Weber’s “Wolf’s Glen” scene.

Phantasmagoria were invented by the scientist-inventor Etienne-Gaspard Robertson (born E. G. Robert in Liège in 1763) and first presented to the public in Paris in March 1798. These shows used a refinement of the magic lantern (the ancestor of the modern slide projector), invented by Athanasius Kircher in the mid-seventeenth century. The refinement made ghosts appear, move about, and disappear in a darkened room before forty to sixty spectators. These shows served as an outlet for the need for mystery and the supernatural denied by enlightened rationality in the Napoleonic age.

Newcomb’s hypothesis is that Weber tried to reproduce the effects of phantasmagoria shows, and that he knew these effects well by the time he began to consider the possibility of a Freischütz opera in 1810. Weber most likely understood the rising popularity of the new paratheatrical entertainments and saw the utilization of this new technology as a way to please the public.

In his article, Newcomb describes several reports of phantasmagoria in early nineteenth-century German cultural journals. He notes, “A report of the Leipzig St. Michael’s Fair of December 1805 remarks that the ‘Geistererscheinungen’ [‘ghostly Appearances’] announced on the first day failed to take place because the entrepreneur, together with the evening’s receipts, disappeared permanently ‘in front of the angry public.’” 17 Newcomb also mentions an article regarding a summer fair in Munich, where the correspondent describes the occurrence of certain “transformations,” which were probably produced by Robertson’s methods.18

Newcomb proposes that the possibilities suggested by the phantasmagoria—not only for “ghostly appearances” but also for movement and quick transformation— inspired Weber to stage the traditional scene from the folk tale in a new way. Weber’s music reinforced the scene’s visual imagery and rapid temporal shifts.

Weber may also have had in mind events occurring in opéra comique libretti and productions of 1790–1820. Weber, as Director of the Opera, first in Prague (1813–17) and then in Dresden, filled his repertoire with works by Luigi Cherubini (1760–1842), Etienne-Nicolas Méhul (1763–1817), Nicolas-Marie Dalayrac (1753–1809), and other French composers. Weber turned from Singspiel as his model to the French opéra comique—for example, those works of Cherubini whose plots drew from real life and seized the imagination. Cherubini’s orchestral mastery was to depict natural scenes, or dramatic disasters such as fires, avalanches, and storms, in a manner that delighted a generation inspired by Rousseau’s appeal to Nature as a force in men’s lives. In addition, Der Freischütz surpassed its Singspiel basis since the orchestra is given a greater role, something Weber had admired in Cherubini and Méhul.

Weber never again tried anything as closely derived from popular shows as the “Wolf’s Glen” scene. Although Euryanthe (1823) has its ghost, it does not have real phantasmagoric scenes with quick successions of ghosts and supernatural happenings appearing in the midst of the stage by trick effects of lighting. However, phantasmagoric elements exist in numerous other nineteenth-century opera scenes. The appearance of a phantom ship was already a well-known phantasmagoric effect in productions of The Flying Dutchman in London melodramas in the 1820s, two decades before Richard Wagner’s opera of the same name. Gounod’s early opera La Nonne sanglante (1854) included a specifically phantasmagoric scene.19 The act 3 finale from Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable (1831)—the evocation (and ballet) of the ghosts of nuns in the graveyard of an abandoned convent—is a clear reference to Robertson’s phantasmagoric shows often held in the abandoned Couvent des Capucines.

It is not the influence of phantasmagoria shows in Weber’s “Wolf’s Glen” scene that is the principal focus of this dissertation. It is the one additional element: the offstage choir of “Invisible Spirits.” Of the other above-mentioned selections from operas containing phantasmagorical elements, none includes an offstage chorus, whether with text or wordless. Even Weber’s pupil Heinrich Marschner (1795–1861), quick to seize on the idea of the horrifying as a dramatic subject in his opera Der Vampyr (1827), failed to produce anything as novel as the offstage chorus in the “Wolf’s Glen” scene. The conceptual possibilities for staging opened up by Robertson’s popular entertainments and the connotations and resonances that they brought to theater inspired Weber in a truly unique manner.

The “Wolf’s Glen” scene serves as a prototype of dramatic vocalization. Even though the chorus is hidden, it still sings recognizable syllables during the episodes of vocalization. This text identifies the voices as “human” and not something else entirely otherworldly. It would not be Marschner, Weber’s pupil, who would inherit the dramatic vocalise tradition, nor Meyerbeer or Wagner, but instead Hector Berlioz.

After the premiere of Der Freischütz in Berlin, it was performed in Leipzig, Vienna, Munich, Mannheim, and a number of other Austro-German cities. In Strasbourg, a German troupe performed it in 1822. London saw it in turn on 23 July 1824. A Paris production seemed destined.

François-Henri-Joseph Castil-Blaze—music critic of the Parisian journal Débats since 1820 (under the pseudonym “XXX”) and grand arranger of pastiches containing German and Italian operatic selections—had been invited in 1821 by Jacques-Alexandre- Bernard Law, marquis de Lauriston, to translate into French a dozen foreign operas. Since he was unable to obtain access to the Paris Opéra, Castil-Blaze decided to produce his translations at the Odéon. There on 6 May 1824, he produced Rossini’s Le Barbier de Séville, followed on 4 August by La Pie voleuse, after La Gazza ladra.

Then, the “l’entrepreneur des demolitions dramatiques,” as he was called by the editor of La Pandore, decided to mount Le Freyschütz [sic].20 In the Journal de Paris from 11 October 1824, an ironic note addressed Castil-Blaze:

En attendant que M. Castil-Blaze ait arrangé, pour le Théâtre de Madame

le Chasseur noir de Winter, dont on n’y parle guère que depuis deux ans,

l’Odéon s’apprête à nous le montrer sous le nom de Robin des Bois. On

vient de distribuer les rôles de cet opéra.21

[While waiting for Mr. Castil-Blaze to arrange for the Théâtre de Madame

the Chasseur noir of Winter [sic], about which one has hardly spoken for

two years, the Odéon undertakes to show it to us under the name of Robin

des Bois. He has just distributed the roles of this opera.]

Robin des Bois ou les trios balles, presented on 7 December 1824, was, according to Castil-Blaze, “except for the character of the hermit that the censor had removed, a literal and complete translation of the German work.” 22 Nothing could be more inaccurate. The interpretation of the artists was deplorable; the mise en scène was worse. The first act was met with laughter; the infernal scene of the second act was burlesque. However, the overture was acclaimed and the chorus of hunters in the third act was encored.23

In his column in Débats on 1 December 1824, after giving an announcement of the first performance of Robin des Bois, Castil-Blaze informed his readers that the score would be published on the first of the following February, with subscriptions available 5 December.24 This announcement and the subsequent performances at the Odéon provoked between the publisher Schlesinger, owner of the rights to the piano reduction of Der Freischütz, and Castil-Blaze a polemic that was prolonged until the arrival in Paris of Weber himself in February 1826. Weber had sold his piano reduction to Schlesinger but had reserved the rights to the orchestral score, since according to the practice of the time he could sell copies to the theaters.25

Schlesinger protested against Castil-Blaze’s arrangements, for example against the interpolation, of a “joli duo d’Euryante [sic],” added so that Max (rechristened “Tony” for Robin des Bois) would at one point find happiness. Castil-Blaze later claimed to have conformed to the English version, in the translation by “Livius,” previously performed in London.26 However, Livius, who was in Paris in December 1824, issued a flat denial of these claims. Débats failed to publish Schlesinger’s protests.

In the wake of the immediate success of Robin des Bois, Castil-Blaze was encouraged to participate in the “mutilations” of other works of Weber. For example, La Forêt de Sénart, in three acts after Partie de chasse de Henri IV, given at the Odéon on 14 January 1826, included the storm from Beethoven’s Pastorale symphony, a section of the finale from Weber’s Euryanthe, an aria and a fragment from the finale of Der Freischütz, and diverse selections from Rossini, Meyerbeer, Pacini, Mozart, and Castil-Blaze himself.

Weber was infuriated and made his feelings known in two letters addressed to his “arranger” on 15 December 1826 and 4 January 1827. In the latter Weber writes:

C’est mon intention de monter moi-même cet ouvrage à Paris; je n’ai point

vendu ma partition, et personne ne l’a en France: c’est peut-être sur une

partition gravée pour piano que vous avez pris les morceaux dont vous

voulez vous servir. Vous n’avez pas le droit d’estroper ma musique, en y

introduisant des morceaux dont les accompagnements sont de votre façon.

C’est bien assez d’avoir mis, dans le Freyschütz, un duo d’Euryanthe, dont

L’accompagnement n’est pas le mien. . . . J’aime à oublier le tort qu’on

M’a fait; je ne parlerai plus du Freyschütz, mais finissez-là, monsieur, et

laissez-moi l’espérance de pouvoir nous rencontrer une fois avec des

sentimens dignes de votre talent et de votre esprit.” 27

[It is my intention to assemble this work for Paris myself; I did not sell my

score, and no one in France has it: it is perhaps a score engraved for piano

that you took the pieces of, which you want to use yourself. You do not

have the right to mutilate my music by introducing pieces whose

accompaniments are yours. It is enough to have put in Freischütz a duet of

Euryanthe, whose accompaniments are not mine. . . . I would like to forget

the wrong that you have caused me; I will not speak any more of

Freischütz, but finish there, Sir, and leave me the hope of being able to

meet you with sentiments worthy of your talent and spirit.]

The January edition of Le Corsaire published Weber’s two letters, which were followed on 1 February by a third written by Schlesinger, sympathetic to Weber’s perspective.

Meanwhile, Castil-Blaze inserted in the issue of 25 January a reply to Weber where he gave rather weak reasons for his conduct. He claimed that the Germans, like the Belgians, the English, the Dutch, etc., steal French opéras-comiques. As for Robin des Bois, he wrote that he:

était imité du Freyschütz, ce qui annonce les changements dont l’auteur se

plaint et dont l’arrangeur se félicite. En effet, le Freyschütz arrive à Paris,

précédé par une réputation extraordinaire; après bien des invitations, je me

décide à le traduire avec mon collaborateur qui s’en était déjà occupé. Je

résolus de ne rien changer à la musique; je tins parole, autant que les

convenances de notre scène me le permettaient. Qu’arriva-t-il? Tout le

monde le sait. La pièce fut sifflée et resifflée. Voyant que cet opéra ne

pouvait se tenir sur ses jambes, j’imaginai de l’estropier, et je le fis avec

tant de bonheur que, depuis lors, il a marché d’un tel pas que l’on ne sait

point s’il doit s’arrêter un jour, et cent cinquante-quatre représentations

viennent justifier l’opération de l’arrangeur. 28

[imitated Freyschütz, and announced the changes that the author complains

about and with which the arranger is pleased. Indeed, Le Freyschütz arrived

in Paris preceded by an extraordinary reputation; after many invitations, I

decided to translate it with my collaborator who was already occupied [with

the project]. I was resolved not to change the music; I sent word, as much as

the suitabilities of our scene permitted me. What happened? The entire

world knows. The piece was whistled and re-whistled. Indicating that this

opera could not stand on its own legs, I thought of the mutilation, and I did

it with happiness as well. Since then, it has gone at such a pace that one

does not know if it is ever going to stop, and a hundred and fifty-four

performances justify the work of the arranger.]

Weber arrived in Paris on 25 February and spent five days there before embarking for Calais. Among the many visits he made to artists and friends, he carefully avoided meeting Castil-Blaze, and took care not to enter the Odéon.

Composer Hector Berlioz (1803–69) wrote an entry in his memoirs regarding the production of Robin des Bois, Weber’s arrival in Paris, and his negative assessment of Castil-Blaze’s transcription:

While thus absorbed in my musical studies and while my fever for Gluck

and Spontini and my aversion from the Rossinian forms and doctrines

were alike at their height, Weber appeared on the scene. The Freischütz

was given at the Odéon, not in its own beautiful form, but in a distorted,

disfigured, vulgar “adaptation” bearing the title of Robin des Bois. The

orchestra, which was a young one, was excellent, and the chorus fair, but

the singers were atrocious. One of them alone, Mdme. Pouilly, who played

the part of Agatha (rechristened Annette by the translator), possessed a fair

amount of execution, but nothing else, the result being that the part, being

sung without intelligence, passion, or fervor, was virtually annihilated.

She sang the grand air in the second act with as much feeling as if it had

been one of Bordogni’s exercises, and it was not until long afterwards that

I discovered what a mine of beauty it contains. 29

The first performance was greeted with a storm of laughter and

hisses; but on the second night the waltz and the huntsmen’s chorus,

which had excited attention from the first, created such a sensation that

they saved the rest of the work, and it drew full houses every night. . . .

Lastly, the devilries in the Wolf’s Glen were tolerated as comic. All Paris

flocked to see so outlandish a piece; the Odéon thrived on the proceeds;

and M. Castil-Blaze received over a hundred thousand francs for

mutilating a masterpiece.

Prejudiced as I was by my exclusive and intolerant idolatry for the

great classics, I was nevertheless overwhelmed with surprise and delight at

Weber’s music. Even in its mutilated form I was positively intoxicated by

its delicious freshness and its wild, subtle fragrance. To a man sated by the

staid solemnity of the tragic muse, the rapid action of this wood-nymph,

her gracious brusqueries, her dreamy poses, her pure maidenly passion,

her chaste smile, and her sadness, brought a torrent of new feelings and

emotions. I forsook the Opéra for the Odéon, and, as I had a pass to the

orchestra, I soon knew the Freischütz (as there given) by heart. 30

Berlioz continues:

When Weber saw what a hash Castil-Blaze, that veterinary surgeon of

music, had made of his Freischütz, he was very angry, and his just

indignation found vent in a letter that he published before leaving Paris.

Castil-Blaze had the audacity to reply that it was very ungrateful of M.

Weber to reproach the man who had popularized [sic] his music in France,

and that it was entirely owing to the modifications of which the author

complained that Robin des Bois had succeeded!

The wretch! . . . and to think that a miserable sailor is punished

with fifty lashes for the least act of insubordination! 31

Berlioz’s judgments reflect his agreement with Weber’s views at a time when support of them would produce beneficial results for his own works using similar means and methods. In addition, Berlioz’s claim to have known Der Freischütz “by heart” should not be underestimated, since examples from the opera figure prominently in his later Grand traité d’instrumentation et d’orchestration (1844).

(Nauman 2009, 17–35)

Examples | Comments |