Dramatic Vocalise Database

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958)

Sinfonia Antartica [#7] (1952)

It is clear from an essay Vaughan Williams wrote in 1944, “Film Music,” that he greatly enjoyed writing for the genre.

I still believe that the film contains potentialities for the combination of all the arts such as Wagner never dreamt of.1

As regards the score to Scott of the Antarctic, Ursula Vaughan Williams states:

The longest, and perhaps most musically inventive of the eleven for which he produced scores was Scott of the Antarctic, for Ealing Studios, where the Director of Music was Ernest Irving, who became a friend and admired colleague. The idea of great, white landscapes, ice floes, the whales and penguins, bitter winds and Nature’s bleak serenity as a background to man’s endeavor captured RVW’s imagination. He conjured dramatic and icy sounds from the orchestra, added xylophone and vibraphone to the more usual instruments and used, as well, a small chorus of soprano and alto voices, led by a soprano soloist.2

The score for Scott of the Antarctic, composed in 1947–48, so engaged the composer that he wrote some of the music well in advance of the actual scenes being shot. The film was first shown in London on 29 November 1948; the soundtrack was a recording of the Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Ernest Irving.

Just as thematic material from the opera The Pilgrim’s Progress (1949, rev. 1951–52) would be a part of his own Fifth Symphony (1938–43, rev. 1951), so Vaughan Williams adopted music from his score for Scott of the Antarctic for a symphony. According to Ursula Vaughan Williams:

RVW had written so much Antarctic music that is was not long before he was sure of its symphonic possibilities and he set about re-organizing and reshaping his work. He had been fascinated by the instruments he had used to signify the strangeness of the polar world, orchestral sounds which he re-used with dramatic effect.3

The ensuing Sinfonia Antartica was composed between 1949–52, and is dedicated to Ernest Irving, conductor of the film score.

The full score of the symphony gives the following information regarding the premiere:

This work was first performed on 14 January 1953 in Manchester by the Hallé Orchestra, conducted by Sir John Barbirolli, who have also recorded it for H.M.V. Some of its themes are taken from the music written for the film “Scott of the Antarctic” (Ealing Studios).4

The premiere at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester featured Margaret Ritchie (soprano) and the women of the Hallé Choir, in addition to the Hallé Orchestra. The first performance in London occurred a week later on 21 January, again with Margaret Ritchie as soprano soloist, at a Royal Philharmonic concert at the Royal Festival Hall.

Although Vaughan Williams left no indication in the score as to the placement of the solo soprano and women’s (SSA) chorus, a review of the premiere in 1953 tells of its location:

The vast orchestra includes almost everything that tinkles, jingles or bangs, even bells, a vibraphone and a wind-machine, as well as women’s voices without words. (At the first performance the singers were placed off-stage.)5

The wordless aspect of the chorus drew the attention of Michael Kennedy:

Here again

Kennedy again touches upon the subject of the wordless chorus within the same article when he descriptively writes (with perhaps a reference to Debussy) of “the voices howling like sirens of the snows in the blizzard in Sinfonia Antartica.” 7

Music that accompanies bleak images of ice, of glaciers, and the sea in the film, appears in the first and last movements of the symphony, and is built upon the same motive previously mentioned in regards to Vaughan Williams’s earlier works. The vocalization in the first movement of Antartica also has a melodic content and contour very similar to the end of Maurya’s elegy in Riders to the Sea.

Vaughan Williams, Sinfonia Antartica, mvt. 1, mm. 68–75

8As in the ending of that opera, a solo soprano voice sings a descending figure accompanied by interspersed rocking undulations from the women’s choir singing the Ravel-like motive also found in Vaughan Williams’s earlier works. Another representative example, and one that again shows the two themes juxtaposed against one another, comes from further in the same movement.

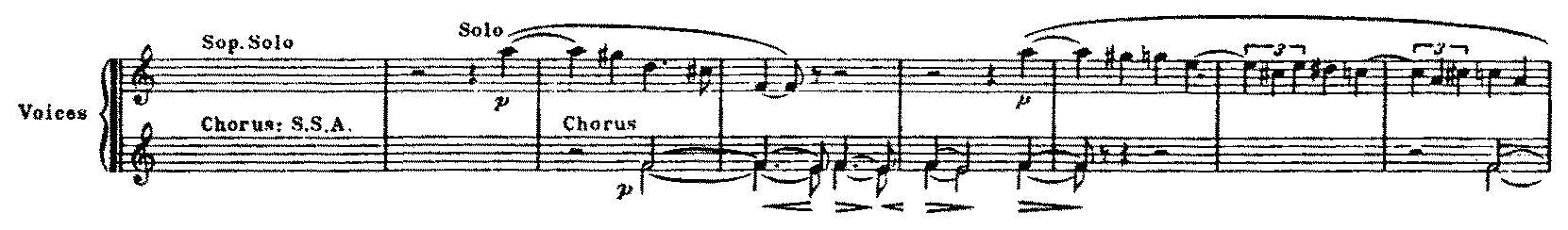

Vaughan Williams, Sinfonia Antartica, mvt. 1, mm. 139–50

9The first and last of the five movements, “Epilogue” and “Prologue” respectively, share similar thematic material and are the only ones that include the chorus and soprano soloist. As Colin Mason notes in his review of the premiere of the symphony:

[The two outer movements] contain the symphonic essence of the work. They are at once the least and the most pictorial movements: for it is in them that the women’s voices and the wind machine are used to depict most graphically the vast desolation of the Antarctic, yet it is they that have the themes of the most symphonic cut, developed the most extensively and “symphonically.” Even these themes, with their strong intervals and constant thrust upwards, express something extra-musical: not anything that can be painted, but the unconquerable spirit of aspiration suggested by the quotations written above the two movements in the score.10

The quotations given in the printed score for the outer movements are as follows:

Movement 1:

To suffer woes which hope thinks infinite,

To forgive wrongs darker than death or night,

To defy power which seems omnipotent,

Neither to change, nor falter, nor repent:

This . . . is to be

Good, great, joyous, beautiful and free,

This is alone life, joy, empire and victory.

– Percy Shelley, Prometheus Unbound11

Movement 5:

I do not regret this journey; we took risks, we knew

we took them, things have come out against us,

therefore we have no cause for complaint.

– Captain Robert Scott, Scott’s Last Expedition12

Colin Mason continues:

The affinity of mood of these two quotations reflects the musical affinity of the two movements. This mood is most nobly and unmistakably expressed in the opening theme of the Prelude, and at the end of the symphony Vaughan Williams recapitulates this whole opening section. The effect is tremendous, conclusive, finally reinforcing the formal and emotional unity of the whole work.13

The similarity between the outer movements is readily apparent through a comparison of the above examples with one from the last movement.

Vaughan Williams, Sinfonia Antartica, mvt. 5, mm. 172–90

14The ending of Sinfonia Antartica is similar to that of Riders to the Sea. Both pieces end with solo wordless soprano with melodic material comprised of the same motive first found in the third of the Five Mystical Songs, and also the Ravel-like theme used to represent the sea.

William Kimmel, in his article on Vaughan Williams’s melodic style, notes the similarities among these pieces:

Far more characteristic from the formal point of view . . . are the very free, rhapsodic melodies which may be found in nearly all of the larger works—vocal and instrumental. They are frequently marked “senza misura” and where possible are written without bar lines. Almost completely devoid of harmonic background and of rhythmic regularity or metrical symmetry, they are held together and given coherence by means of a pedal sustained below or above the melody or though some recurring note or figure to which the melody frequently returns. The significance of this type of melody is emphasized not only by the frequency of its use but also by its invariable appearance in prominent places.

A conspicuous feature is the great frequency of triplet figures and their alternation with duplets and quadruplets. It is also characteristic to find repetitions of the same melodic fragment in varying rhythmic patterns.15

Although written in 1941, Kimmel’s notion is equally applicable to Vaughan Williams’s Sinfonia Antartica. In addition, his comments in the second quoted paragraph are equally applicable to works by other composers that include dramatic vocalization such as Debussy’s “Sirènes,” the third movement of Roussel’s Évocations, and the “Lamentations de Guilboa” from Honegger’s Le Roi David.

(Nauman 2009, 184–90)

Examples | Comments |