Dramatic Vocalise Database

Albert Roussel (1869–1937)

Évocations, Op. 15 (1911)

At age twenty-five, after serving in the French navy for seven years, Albert Roussel (1869–1937) decided to become a musician and sent a letter of resignation dated 14 June 1894. Four years later he entered the newly established Schola Cantorum, where he studied under Vincent d’Indy. In 1902, d’Indy entrusted him with the counterpoint class, which he taught until June 1914. Roussel and his wife of a year set sail in 1909 on a three-month voyage to the Indies and Cambodia. The result of this tour was the splendid set of three Évocations, op. 15 (1911) and the opera-ballet Padmâvatî (1919).

Less than a month before the premiere of the orchestral Évocations at the Salle Gaveau on 18 May 1912, Natalie Trouhanova gave a historic ballet recital in Paris, in which three major French compositions of oriental inspiration were included, each being conducted by its composer: La Péri by Dukas, d’Indy’s Istar, and the first staged performance of La Tragédie de Salomé by Florent Schmitt. Yet Évocations has little in common with any of these works. According to Basil Deane, “It is richer and more subtle than Istar, less complex and barbaric than Salomé and avoids the enervating Rimskyan chromaticism and rigidity of phrase structure which weaken La Péri. The distinction of the composer’s conception . . . is expressed by a highly individual style.” 1

The three Évocations, composed during 1910 and 1911, were inspired by Roussel’s memories of India, specifically the caves at Ellora, of Jaipur, and of Benares on the banks of the Ganges. Of these, the third uses a chorus with text written by fellow Les Apaches member Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi. According to the librettist:

It had occurred to me, some time before [Roussel’s trip to India], to arrange certain passages of a translation of Kalidasa’s works into short prose poems suitable for musical settings. Five of these, more or less remodeled for the purpose, had been used by Eugène Grassi, the Siamese composer, in his lovely Chansons Populaires Siamoises. The remainder I showed to Roussel, who took them away and, to my great delight, told me a few days later that they had given him the idea of using human voices in the finale of a symphonic triptych which he was composing. He selected three, of which he used two exactly as they stood. But he wished the third to keep to a certain rhythm throughout—the rhythm of a psalmody which he had heard a fakir singing—so that he rewrote it practically from end to end. Thus it is that I had a small share in the genesis of his admirable Evocations.2

This movement is the most significant of the three, not because it uses chorus and soloists, but because of the use of Hindu scales, which anticipates Padmâvatî. According to Norman Demuth, “It is . . . by the use of the Hindu scales that Roussel succeeds in giving distinction to the work and moving it outside the borders of sheer French impressionism.” 3

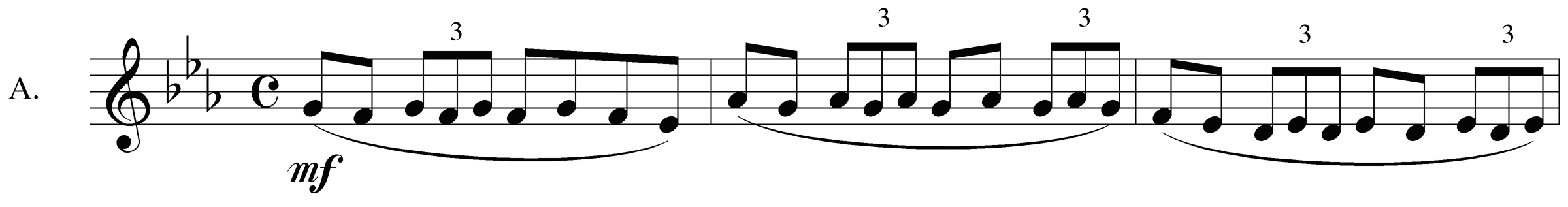

The opening of the last movement “Aux bords du Fleuve Sacré” conjures up night falling over the banks of the Ganges, as is made clear by the text of the following chorus entry. In the next section the sopranos describe couples embracing in the moonlight, accompanied by the vowel “A” in the other voices (mm. 88–95). This is followed by a passage for the full chorus singing “A” (mm. 98–117), then “Au” (mm. 118–139). The musical material in the chorus at times is highly reminiscent of Debussy’s Siren theme—the undulating women’s voices moving by step in alternating duple and triple subdivision.

Roussel, Évocations, op. 15, mvt. 3, mm. 122–24

Immediately preceding the entrance of the solo tenor, the music once again seems to evoke Debussy’s “Sirènes,” especially the soprano part in measure 139. The tenor, accompanied by wordless women’s chorus, delivers the short phrase: “Mais les parfums de la nuit déjà réveillent dans les c œurs l’amour” [“Yet, already, the fragrances of the night are awakening hearts to love”] (mm. 140–45), before the chorus launches into an extended developmental section of pure vocalization (mm. 145–212), alternating between the vowels “A” and “Au.” The wordless chorus creates an atmosphere of warm voluptuousness, and the music rises to a passionate climax.

Following the extended choral passage, the solo tenor sings of couples embracing in the moonlight, wandering under the leaves, and throbbing with happiness (mm. 213–19), again accompanied by wordless women’s chorus. The following contralto solo follows the tenor’s lead, but now switches to a first-person perspective, accompanied by wordless chorus (ATB) (mm. 241–51). This is followed by the chant of a fakir, an ecstatic chant heralding the break of day (mm. 281–324), followed by a grandiose, solemn hymn to the sun (mm. 332–97).4 In the few closing bars, with consummate skill the composer reintroduces peace and silence on a pianissimo held by the choir and punctuated by the orchestra.

Roussel, Évocations, op. 15, mvt. 3, mm. 138–40

5(Nauman 2009, 106–8)

Examples | Comments |

| mvt. 3 (excerpt) |

Footnotes

1 Basil Deane, Albert Roussel (London: Barrie and Rockliff, 1961), 61.

2 Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi, Music and Ballet (1934; repr., London: Faber and Faber, 1978), 58–59. Calvocoressi had previously translated from Greek to French the text for Ravel’s Cinq mélodies populaires grecques (1904–6). He was also the principal French adviser to Diaghliev when the latter was introducing Russian orchestral music, opera, and ballet to Paris (1907–10).

3 Norman Demuth, Albert Roussel (1947; repr., Westport, CT: Hyperion, 1979), 50.

4 Pietro Mascagni’s Iris also contains a “Hymn of the Sun.”

5 Albert Roussel, Évocations: Aux bords du Fleuve Sacré, op. 15, no. 3 (1912; repr., Miami, FL: Kalmus, 1988), 32.