Dramatic Vocalise Database

Pietro Mascagni (1863–1945)

Iris (1898)

It would be nearly fifty years after Verdi’s Rigoletto, until the premiere of Iris by Pietro Mascagni (1863–1945) on 22 November 1898 at the Teatro Costanzi, before another Italian composer included dramatic vocalization within an operatic work. Mascagni conducted the performance; in attendance were Queen Margherita, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Giacomo Puccini, Alberto Franchetti, Arrigo Boïto, Siegfried Wagner (Richard Wagner’s son), and critics from the most important newspapers. The librettist Luigi Illica’s heavy-handed symbolism mystified some of the audience. Although the prelude, the “Inno del sole” [“Hymn of the Sun”], was encored, critical reaction to the work as a whole was cool. In the words of Edoardo Pompei:

The critics, with a few exceptions, were generally severe on the new work. Sharp spears were launched against the libretto, which was judged empty, vague, and incapable of sustaining the least bit of interest—and Mascagni was reproached, with unusual rigor, for his harmonic practices and his abstruse instrumentation. For the majority of critics, Iris was an absolutely unsuccessful opera.1

Despite mixed reviews, audiences flocked to the new opera. Even hostile critics recognized that, whatever their own feelings, the work was a temporary hit with the Roman audience. Iris was performed fourteen times.

The story is set in a mythical Japan before its nineteenth-century opening to the West. Innocent and beautiful, Iris lives with her blind father in a cottage in the shadow of Mount Fuji. In the opening scene of act 1, a succession of orchestral tone poems illustrates the night [La Notte], flowers [I Fiori], and the coming dawn [L’Aurora]. The sun arrives and warmly greets all living things with its comforting message of life, beauty, and love. An offstage chorus representing the voice of the rising sun sings “Son Io! Son Io la Vita! Son la Beltà infinita, la Luce ed il Calor.” [“It is I! It is I, Life! I am infinite Beauty, Light and Warmth.”] Iris wakes and relates a nightmare she has just experienced and thanks the sun for dispelling her terrifying dreams. Meanwhile Osaka, a young nobleman, and Kyoto, owner of a geisha house in the Yoshiwara (the red-light district of the city), spy upon Iris in her garden since Osaka is attracted to her and has engaged Kyoto to abduct her.

Osaka and Kyoto leave. Iris attends to her garden, the flowers she so loves, as her blind father prays aloud in the sunlight. Osaka and Kyoto return disguised as itinerant puppet players, leading a company of geishas, samurai, and musicians. They set up their puppet theater beside Iris’s garden and commence with their show, telling of the unfortunate Dhia, whose cruel father wants to sell her into slavery. When Dhia prays for deliverance, her plea is answered by the puppet Jor, Son of the Sun (whose voice is supplied by Osaka). Iris, who loves the sun beyond measure, is mesmerized, especially by the puppet Jor. At the end of the play Kyoto’s geisha dancers perform a ballet surrounding Iris, enabling the samurai to stifle her voice and abduct her in secrecy.

Iris’s father, unaware of her abduction, discovers a purse of coins and a note left by Kyoto. One of a group of nearby peddlers, attracted by his cries, reads the note informing him that Iris has gone to the Yoshiwara. Believing Iris has abandoned him of her own will, her father is horrified and broken-hearted. He begs the peddlers to guide him to the Yoshiwara so he may find Iris and curse her.

Illica prefaces all three acts with a passage of long-winded prose describing the situation and events that are to follow. The somber text prior to act 2 provides a substantial contrast to the preceding act, with its glorious “Hymn of the Sun,” the world of light and happiness. Illica instead portrays the Yoshiwara as a place without light, a world of darkness:

Non luce, non l’armonia del Sole! Solo, su dalla tumultuante via, per le stuoie che la dimenticanza delle kamouro ha lasciato semiaperte, entra l’affannoso moto della vita cittadina, le strida dei merciaioli, le minaccie dei samouraïs, le ansanti cadenze dei djin, i diversi idiomi dei dragomanni, la bestemmia e la risata. Presso al tuo letto, come spettri, stanno ancora le guèchas.2

[Neither the sun’s light nor its harmony gain entry here. Only the maddened din of city life—the merchants’ cries, the samurai’s warnings, the rickshaw drivers’ heaving cadence, the coarse accents of workers’ blasphemous oaths and brutish laughter—enters through the shutters, left ajar by the forgetful servant. Close to your bed, like specters, the geishas from the puppet show keep their vigil.] 3

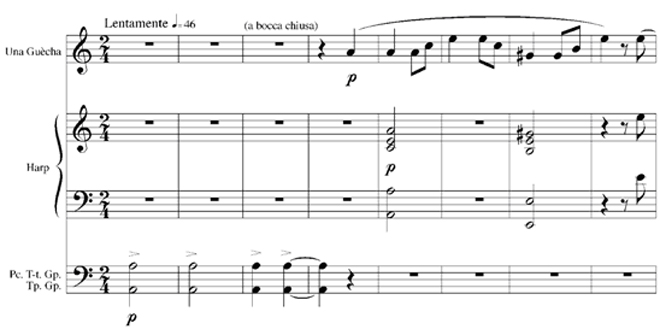

Mascagni translates Illica’s sense of contrast into music by presenting an onstage geisha kneeling in a corner, humming an “Anakomitasani” to the accompaniment of a “samisen,” while Iris sleeps. This minor-key, a bocca chiusa geisha song, accompanied by harp, remains dynamically restrained (pp or p) throughout. The end of each period is punctuated by the strokes of onstage “Strumenti sul Palco” [“Instruments on the Stage”]: “Timpani Giapponesi” and “Piccolo Tam-Tam Giapponesi.” This sparse song serves as an introductory gesture, an opening like an orchestral prelude that foreshadows the impending tragedy. The thin texture and the lamenting melody provide a stark contrast to the preceding act with its glorious “Inno del sole,” the luxuriant garden scene, and the exotic Japanese instrumentation of the puppet show.

Mascagni, Iris, act 2, mm. 1–25

Following the geisha song, Kyoto enters sotto voce, continuing the subdued, hushed tones of the preceding passage. Osaka arrives and after discussion with Kyoto attempts to seduce Iris, plying her with gifts and promises. Unable to charm Iris with his advances, Osaka rejects her. Kyoto, eager to recoup his investment, places Iris on display in the window of his brothel. As crowds gather to admire her beauty, Osaka returns and once again yearns for her. Before he can reach her, her father arrives. Iris cries out in joy, but when her father reaches her, he pelts her with mud, cursing her for having abandoned him. In despair, Iris throws herself from the window into the sewer and is carried away.

After the act 3 prelude, the miniature symphonic poem La Notte [The Night], which opens the opera itself, reappears, this time punctuated by an offstage chorus of women singing a bocca chiusa. A group of rag pickers works along the bank of an open sewer. After scavenging nothing but rocks and weeds they discover a pile of silken garments with Iris wrapped inside. When Iris moves they flee in terror. She is sorrowful, badly hurt, and close to death. She hears the voices of Osaka, Kyoto, and her father, each telling her that life is brutal. As the night ends, the first warm ray of sunshine touches her. The sun proclaims its eternal love in a reprise of the “Inno del sole” as Iris dies. The scene is flooded with golden light. The section from act 1, I Fiori [The Flowers] returns, accompanied by women’s chorus a bocca chiusa. The desolate landscape is engulfed by flowers, upon whose leafy tendrils Iris’s innocent, flowerlike soul is triumphantly borne to paradise.

Despite its many charms, Iris is dramatically weak because Illica hobbles his straightforward melodrama with a heavy burden of symbolism. The abduction, the lovemaking, the father’s brutal denunciation, the plunge into an open pit—these are all well-worn materials of the nineteenth-century melodramatist’s trade. In addition, there are repeated generalizations about the emptiness of urban life and simple pleasures of sunshine and flowers, ponderous references to the cruelty of the world and the kindness of Death, and fastidious allusions to snowcapped Fujiyama and pale gray bamboo.

Ultimately, given the undeniable appeal of Mascagni’s score, the best way to approach Iris is to ignore its dramatic shortcomings and to regard it as a fairy tale, with a fairy tale’s happy ending. One must suspend all fashionable sophistication and allow sentiment to take over. Only then can one experience the full measure of emotional gratification when the battered child is borne to paradise on the golden rays of the sun and on the tendrils of the flowers she so dearly loves.

Mascagni has a significant number of operas to his name and by no means all in the style with which he is commonly associated. The main problem with Mascagni lies in the fact that he did not follow his true instinct, which was for more or less pure verismo, and that he ventured into spheres for which his gifts were less well suited. Iris, however, represents the first excursion by a modern Italian opera composer into the alluring atmosphere of legendary Japan and may well have kindled in Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) the desire to try his hand at a similar subject. Puccini’s Madama Butterfly (1904) is of course far superior, but Iris displays harmonic and orchestral subtleties with which we would not have credited the composer of the coarse-grained Cavalleria Rusticana. Mascagni, like Puccini after him, knew how to turn to advantage devices from Debussy, whose music began to cross the Alps in the late 1890s.

Certainly Iris’s initial success with the general public was such that it might have remained in the standard repertoire had Puccini not written Butterfly. In fact, Puccini was among those who criticized Iris from the start. Writing to Alberto Crecchi on 21 January 1899, Puccini states:

Per me quest’opera che ha in sè tante cose belle e uno strumentale dei più smaglianti e coloriti, ha il difetto d’origine: l’azione che non unteressa e si diluisce e langue per tre atti. . . . Tu che gli sei amico vero, digli che ritorni alla passione, al sentimento vivo, umano, col quale iniziò tanto brillantemente la sua carriera.4

[For me this opera, which has such beautiful things in it and is scored in a most brilliant and colorful way, has this fundamental defect: the action is not interesting and languishes and flags for three acts. . . . You, who are his true friend, should tell him that he ought to return to the passion and the lively and human feelings with which he began his career in such a brilliant manner.]

Even so, Puccini was quick to remember the best features of the music when he came to write Butterfly.

(Nauman 2009, 56–64)

Examples | Comments |

| Act 2 (opening) |

Footnotes

1 Quoted in Alan Mallach, Pietro Mascagni and His Operas (Boston: Northeastern University, 2002), 123.

2 Pietro Mascagni, Iris (Milan: Ricordi, 1898), two unnumbered pages between 254 and 255.

3 Translation by Barrymore L. Scherer, liner notes to Iris, by Pietro Mascagni, CBS M2K 45526, 100.

4 Eugenio Gara, ed., Carteggi Pucciniani (Milan: Ricordi, 1958), 173.