Dramatic Vocalise Database

Florent Schmitt (1870–1958)

La Tragédie de Salomé, Op. 50 (1907)

Born in Blâmont, Lorraine, in 1870, Florent Schmitt entered the Paris Conservatoire in 1889, where he studied harmony with Dubois and Lavignac, and composition with Massenet and Faur.1 His first attempt at the Prix de Rome gained him the second prize in 1897. Three years later he won the Grand Prix. He composed prolifically during his Rome sojourn, traveling afterward to Germany, Austria, Turkey, and North Africa. Upon his return to Paris in 1906, an all-Schmitt concert was given at the Conservatoire. During the next four years he solidified his reputation with Psalm XLVII, op. 38 (1904), and La Tragdie de Salomé.

Schmitt completed La Tragdie de Salom in 1907 and dedicated the score to Stravinsky. It was first performed on 9 November of the same year at the Théâtre des Arts in Paris, with Désiré Inghelbrecht, also a member of Les Apaches, conducting. In its original form the work was conceived as a choreographic poem. Later, the composer arranged it as a concert suite, after considerably amplifying the orchestration.

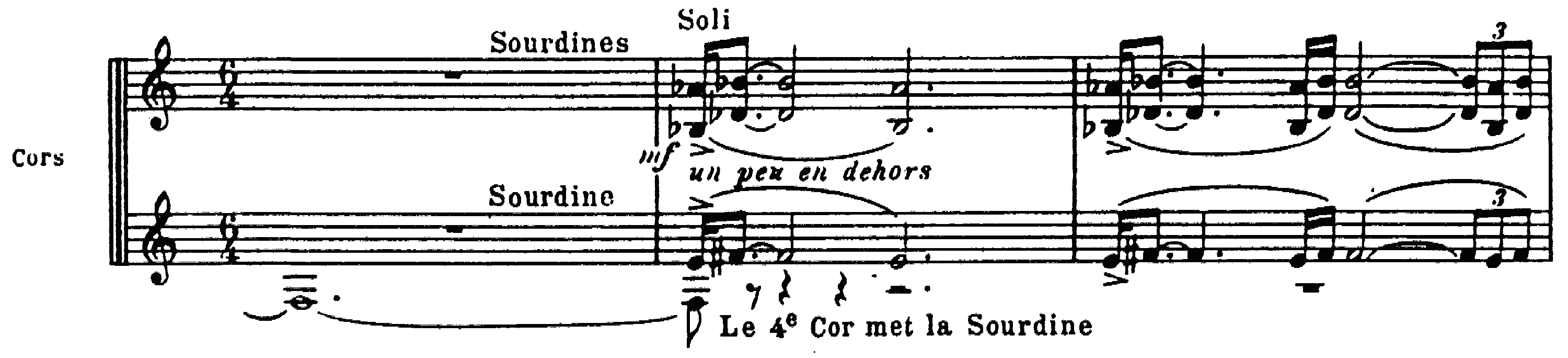

Based on a poem by Robert d’Humières, La Tragédie de Salomé closely follows the action of the text. At the opening of the second movement, “Les enchantements sur la mer,” one is immediately confronted with something very similar to the opening measure of Debussy’s “Sirènes”: the rumbling of low strings, tremolo upper strings, and an initial theme presented by muted horn trio.

Schmitt, La Tragédie de Salomé, op. 40, mvt. 2, mm. 19–21

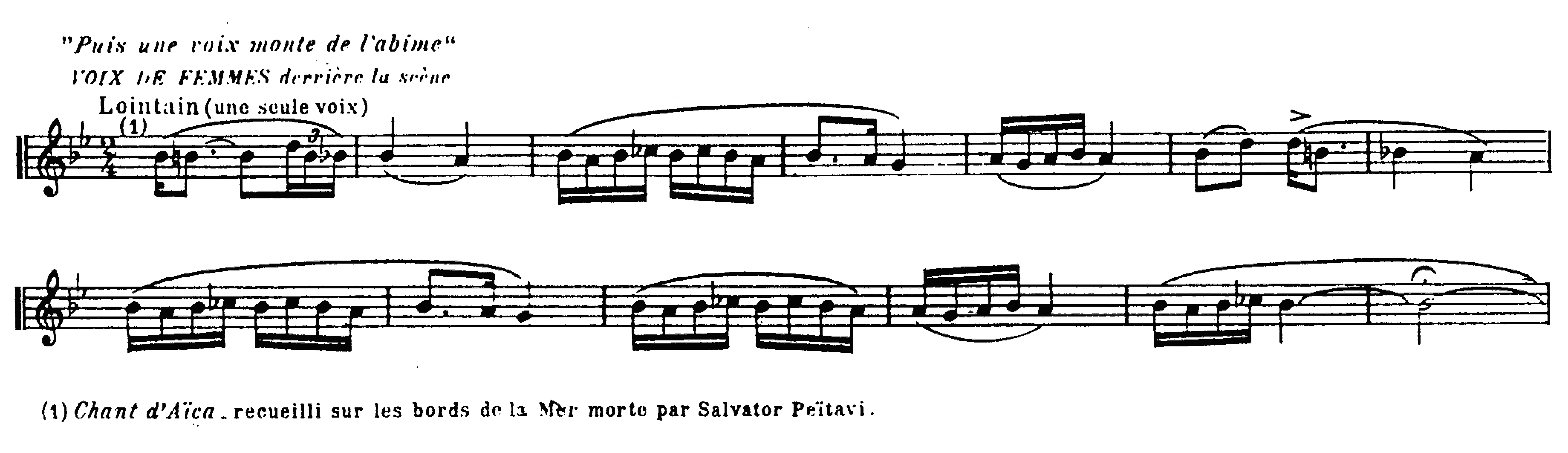

2One would soon expect a response from the chorus, again echoing the horns, and yet Schmitt fails to provide such a direct connection. Instead, a solo soprano accompanied by solo oboe vocalizes an “Eastern” sounding melody, indicated in the score as “Chant d’Aïca, collected on the shore of the Dead Sea by Salvator Peïtavi”.

Schmitt, La Tragédie de Salomé, op. 40, mvt. 2, mm. 89–101

3The score indicates: “Puis une voix monte de l’abîme” [“A voice is heard from the abyss”]. As the music progresses, this melodic idea is taken up by the entire offstage female chorus in three-part harmony while the scene continues to build toward its dramatic climax. Directions given in the score for this section state:

Une voix solitaire s’élève. Elle monte des profondeurs de la Mer Morte, plane sur les abîmes du Passé, du Désert, du Désir. Hérode, subjugué, écoute. Des vapeurs, à présent, s’élèvent de la mer, des formes enlacées se dessinent, montent de l’abîme, vivante nuée dibt soudain, comme enfantée par le trouble songe et l’antique péché, surgit, irrésistible, Salomé. Un tonnerre lointain roule. Salomé commence à danser. Hérode se lève.4

[A solitary voice rises. It rises from the depths of the Dead Sea, and floats over the abysses of the Past, of the Desert, of Desire. Herod, subjugated, listens. Vapors now rise out of the sea; the intertwined forms take shape, arise from the abyss; and alive, cloudy, suddenly, as though engendered by troubled dream and ancient sin, emerges, irresistible, Salome. The sound of thunder is heard in the distance. Salome begins to dance. Herod rises.]

The horn motive is especially reminiscent of Debussy. Just as in “Sirènes,” vocalization is blended into the orchestral texture.

(Nauman 2009, 97–99)

Examples | Comments |

| mvt. 2 (excerpt) |

| mvt. 2 (excerpt) |

| mvt. 2 (complete) |

Footnotes

1 Schmitt’s teacher Jules Massenet (1842–1912) provided an optional offstage humming-chorus for the famous “Méditation” from his opera Thaïs (1894), signifying the protagonist’s religious conversion.

2 Florent Schmitt, La Tragédie de Salomé (Paris: Durand, 1913), 73.

3 Ibid., 95.

4 Ibid., [ii].