Dramatic Vocalise Database

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958)

Riders to the Sea (1937)

In 1925, the same year as the premiere of Flos Campi, Vaughan Williams began to sketch his miniature operatic masterpiece Riders to the Sea. Although completed in 1932, it was first performed in London under Malcolm Sargent at the Royal College of Music on both 30 November and 1 December 1937, five years after its completion.1

Vaughan Williams based his opera on the play Riders to the Sea written by Irish playwright J. M. Synge, and first performed on 25 February 1904 at the Molesworth Hall, Dublin by the Irish National Theater Society. Vaughan Williams did not commission a libretto either to expand or contract Synge’s lines. Instead he set the dialogue almost without alteration; indeed he did not call the work an opera but rather a setting of the play.

A one-act tragedy, Riders to the Sea is based on Synge’s experiences on Inishmaan, the middle of the three Aran Islands that lie at the mouth of Galway Bay off the west coast of Ireland. Like all of Synge’s plays it is noted for capturing the poetic dialogue of rural Ireland. The plot of Vaughan Williams’s setting is as follows:

After a short prelude depicting a stormy sea, Nora (soprano) asks her sister Cathleen (soprano) to help her identify some clothes taken off a drowned man as belonging to their brother, Michael. Like his father and four other brothers, he has lost his life at sea. They talk quietly because their mother Maurya (contralto) is resting in the next room, and they hide the clothes in the loft.

But Maurya cannot sleep. She is worried that her last surviving son Bartley (baritone) is taking horses in a boat to Galway Fair. Bartley arrives to fetch a rope. The women beg him to stay, but he tells them how to manage while he is away. He will ride the red mare with the grey pony behind. The sisters reproach Maurya for not giving Bartley her blessing and send her after him with some bread. While Maurya is away, the sisters confirm that the clothing was Michael’s but hide it from their mother. Maurya returns in some distress. She has seen Bartley riding to the sea on the red mare, with Michael, in new clothes and shoes, on the grey pony. Cathleen tells her Michael is dead. Maurya says her vision means Bartley will die too. As she sings of the deaths of her men, Bartley’s body is carried in. He has been knocked into the sea by the grey pony. Maurya, in a noble elegy, sings that the sea can hurt her no more. She blesses the dead and the living.2

Synge’s book on the Aran Islands includes a description of keening [caoine] at the graveside (representation of which figures prominently in Vaughan Williams’s score):

While the grave was being opened the women sat down among the flat tombstones, bordered with a pale fringe of early bracken, and began the wild keen, or crying for the dead. Each old woman, as she took her turn in the leading recitative, seemed possessed for the moment with a profound ecstasy of grief, swaying to and fro, and bending her forehead to the stone before her, while she called out to the dead with a perpetually recurring chant of sobs.

All round the graveyard other wrinkled women, looking out from under the deep red petticoats that cloaked them, rocked themselves with the same rhythm, and intoned the inarticulate chant that is sustained by all as an accompaniment.3

Traditional moments for sounding the caoine are (by members of the family) when death first occurs, then (by professional keening women) as the body leaves the house for the last time, and again at the graveside. The caoine is often called a lament, yet although similar, a traditional lament is a more elaborate and personal expression of loss, usually done by the bereaved. It does not have the ritual character of the caoine, nor does it recount the virtues of the deceased.

The first instance of dramatic vocalization, of keening, by offstage wordless women’s chorus occurs as Maurya describes the death of her husband, father-in-law, and six sons. As she sings of her drowned sons Stephen and Shawn the chorus enters.

Vaughan Williams, Riders to the Sea, mm. 430–36

4A footnote for the above example states the following:

Chorus almost inaudible at first, gradually getting louder (sing on closed “Ah” (er) when soft; open “Ah” when loud.5

The offstage chorus sings an undulating pattern similar to that found in both Flos Campi and Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé.

After Maurya enumerates her losses she realizes her fate, singing, “They are all gone now, and there isn’t anything more the sea can do to me.” Her heart is now free from worry from the sound of the sea, and the separate onstage women’s chorus “keens” a figure similar to the previous one.

Vaughan Williams, Riders to the Sea, mm. 504–10

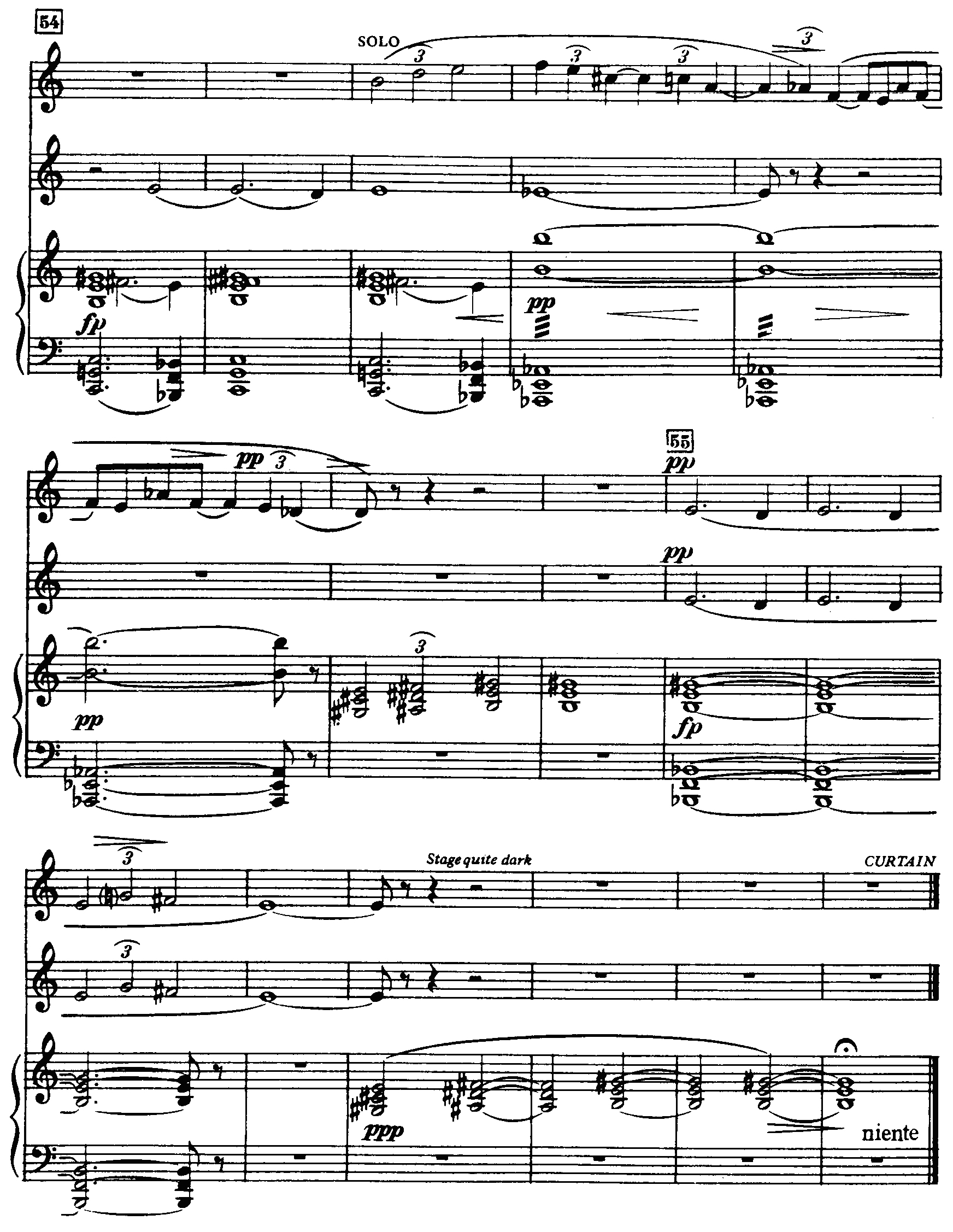

6At the end of her elegy, and the opera, Maurya kneels beside the bier, the cottage door blows open, the roar of the sea is heard, and an offstage wordless soprano, accompanied by the offstage women’s choir, leads the music into quiet extinction.

Vaughan Williams, Riders to the Sea, mm. 622–37

7The chorus sings the rocking Ravel-like theme representing the sea, and the thematic material of the solo soprano—and the entire score—is permeated by the same motive found in the third of the Five Mystical Songs, the Pastoral Symphony, Flos Campi, and Sir John in Love.

Regarding the opera as a whole, Simon Mundy states:

Riders to the Sea is a masterpiece of compression which in a few pages of dialogue conjures up multiple layers of emotional response to the natural world; a losing battle with the sea and the God which rules it for the islanders in the North Atlantic. It is a tragic story in which the women are left to manage their grief and loneliness while the men are all consumed by the sea. Yet finally it is a story of the relief which can come from the end of trouble and the calm of resignation.8

Hugh Ottaway echoes similar sentiments in his article on Riders to the Sea:

Synge’s drama creates a situation in which plain, unsophisticated people are at the mercy of an environment infinitely stronger than themselves. The sea is their destruction, yet they cannot avoid it, for it also provides them with the necessities of life. If struggle is called for, then so is resignation: beneath the outward cataclysm of their lives is a strange repose, a tragic faith in a merciful and benevolent God.9

In choosing this one-act play about Aran fisher-folk, Vaughan Williams found an outlet for a theme to which he was to return in the film Scott of the Antarctic: human endurance in the face of the natural elements. The keening of the women in Riders to the Sea becomes the disembodied voices of the polar winds in the cinematic soundtrack.

(Nauman 2009, 177–83)

Examples | Comments |