Dramatic Vocalise Database

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958)

Flos Campi (1925)

Vaughan Williams again returned to wordless singing/dramatic vocalization shortly after his Pastoral Symphony, in Flos Campi (1925), a suite for viola, orchestra, and wordless chorus. A review of the premiere the following month in the Musical Times provides specific details regarding the performance:

The first of Sir Henry Wood’s Saturday afternoon symphony concerts at Queen’s Hall, on October 10, was distinguished by the production of a new composition by Dr. R. Vaughan Williams—“Flos Campi,” a suite for viola solo (Mr. Lionel Tertis), small orchestra, and wordless chorus (R.C.M. students). Sir Henry conducted. The composer was present, and was called to the platform at the end.1

The word “suite” is misleading since the six movements that comprise the piece, while distinct, follow one another without a significant break. The work is more like a free-flowing rhapsody, a symphonic poem, or fantasia in six subdivisions. Each of these sections is prefixed with a quotation in Latin from the Song of Solomon, but while these provide a clue to the meaning of the music, they are never sung. The chorus intones specified vowels instead of words, and is given such indications as “Extreme head voice. Lips nearly closed. (‘ur’),” “(M) closed lips,” “(open) Ah,” etc. The chorus is present in each of the six movements, of which select excerpts will be discussed here.

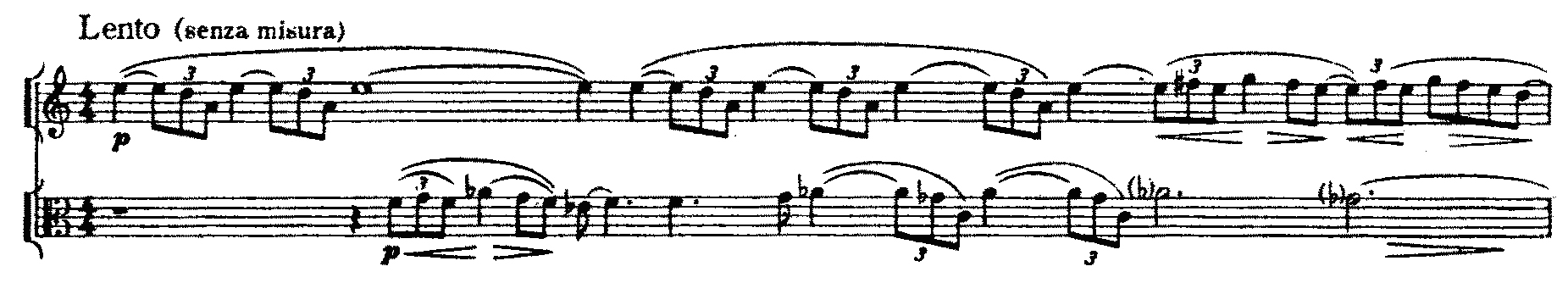

The piece opens with a rhapsodic, bitonal dialogue between oboe and viola, the oboe repeatedly presenting a variant of the vocal motive from the fourth movement of the Pastoral Symphony, echoed by the viola, before the entrance of the strings con sordino.

Vaughan Williams, Flos Campi, mvt. 1, m. 1

2This opening is also marked Lento (senza misura) and lacks bar lines, like the sections with solo voice in the Pastoral Symphony. After these ideas are developed in the orchestra, the chorus finally enters, singing the vowel “Ah.”

The third movement begins with a viola cadenza comprised of the motivic material of the opening oboe solo, followed by the chorus with a motivic idea similar to the primary choral theme in Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé.

Vaughan Williams, Flos Campi, mvt. 3, mm. 97–106

3Following a climax for full orchestra, and another viola cadenza, the opening oboe motive, harmonized and in rhythmic augmentation, appears (for the only time in the piece) sung by the chorus.

Vaughan Williams, Flos Campi, mvt. 3, mm. 124–25

4The final movement is a D-major benediction, which Herbert Howells referred to as a “diatonic fulfillment of longing.” 5 The simple chant-like melody heard at the opening is highly reminiscent of “O Sacrum Convivium,” the ending section of “Love bade me welcome,” the third of the Five Mystical Songs.

Vaughan Williams, Flos Campi, mvt. 6, mm. 261–66

6Eventually the chorus enters (m. 313), singing this same material for thirty-five measures over a sustained pedal D in the strings before fading away (niente). Suddenly the oboe and viola interrupt with the material from the opening of the work before the chorus resumes its benediction. The final chord, an unresolved dissonance, suggests that the mystery, whatever it may be, remains unresolved.

In a 1929 review of the first published full score (1928), the editor of the Musical Times used the term “mystic” in reference to Flos Campi, recalling Holst’s earlier “Neptune, The Mystic” from The Planets, and Vaughan Williams’s Five Mystical Songs.

“Flos Campi” is an exquisite, delicately-intentioned movement, filled with what, for lack of a more exact nomenclature, we must call the mystic element that rides tandem with that other signal influence, the folk-song. Let no chorus lightly undertake the task of performing this work. Not lightly, but with close attention. It will be worth the labor when the time comes for joining forces with the orchestra that has been so finely written for.7

The association between “mysticism” and Vaughan Williams’s style during this period, in particular Flos Campi, was echoed in later articles, and even subtly criticized in Edwin Evans’s review of the premiere performance of Vaughan Williams’s “masque” Job in 1931.

In writing of Vaughan Williams there is one word which comes so readily to the pen as to have become, by frequent usage, a pitfall. It is the word “mystic.” Applied to his “Flos Campi” or “Sancta Civitas” it accurately describes the quality of the music.8

Not all were as accepting of Vaughan Williams’s radical new work as his previous pieces, and in this case the wordless chorus drew criticism from A. E. Purdy in a 1930 Musical Times review of the premiere:

In his report of the recent performance of Vaughan Williams’s “Flos Campi,” “R.C.” writes, in the Daily Mail: “The wordless chorus is the drawback of this work.” I entirely agree. The color of the human voice does not blend with those of the orchestra, and its usage there, shorn of its natural office, the gift of speech, adds nothing to the artistic merit of a musical work; rather it detracts from it. It might be compared to a grey smear over a beautiful painting, obscuring the delicate tints.

The use of the bouche fermée for a small section of a chorus, as found in some part-songs, is legitimate enough, since it suggests a quasi-orchestral (strings or wood-wind sostenuto pp) accompaniment to the other voices. So with the wordless ejaculations, either comic or tragic, met with in opera or revue—which usually have a good effect.

Long stretches of “wordless” chorus-singing in a lengthy orchestral work become tedious immediately after the interest of their novelty has subsided. But are not the singers themselves partly to blame for this policy on the part of composers? The lack of clear enunciation in most chorus-singing, and with many soloists, has become so deep-rooted a complaint that it is small wonder musicians should deem it hardly worth while setting words for people who are too lazy to learn how to articulate clearly. Perhaps this particular weakness was in Vaughan Williams’s mind when he wrote “Flos Campi.” 9

In the following issue an anonymous author, under the pseudonym “Descant,” countered Purdy’s opinion, writing in support of the chorus in Flos Campi.

As one who took part in a recent provincial performance of this truly beautiful and intensely moving work, I would submit, in reply to Mr. A. E. Purdy, that Dr. Vaughan Williams wrote for a wordless chorus for the very simple and all-sufficient reason that nothing else would have achieved the particular tone-color he wished to reproduce. This contention is borne out by the fact that the exact number of instrumental and vocal performers is specified by the composer, so that the requisite balance should be obtained. There are no “long stretches of wordless chorus-singing,” and Mr. Purdy’s remark regarding the “interest of their novelty” makes one conclude that your correspondent looks upon the passages in question as vocalism gone wrong instead of as an integral part of the instrumentation.10

(Nauman 2009, 168–74)

Examples | Comments |

| I. Sicut Lilium inter spinas |

| III. Quaesivi quem diligit anima mea |