Dramatic Vocalise Database

Friedhofer, Hugo (1901–81)

Joan of Arc (1948)

The scores for The Bishop’s Wife (1947) and Joan of Arc, both composed by Hugo Friedhofer (1902–81), are fundamentally intertwined. The very opening of the credits (“Samuel Goldwyn presents”) to The Bishop’s Wife begins with wordless chorus singing two successive chords, before the music continues with just the orchestra alone. These two chords also occur in Joan of Arc when Joan (Ingrid Bergman) magically identifies the disguised Dauphin (José Ferrer) in a crowd.

[See mm. 31–33 in the following example.]

In Joan of Arc, two places in particular emphasize the religious/numinous aspect. While in prison, Joan prays for forgiveness for feeling fear at the prospect of her execution by fire. Dramatic vocalization (including the two-chord motive previously mentioned) sounds as she hears something we cannot. Joan says, “You speak to me, and I denied you.” It is a redemptive moment, one of transformation and forgiveness. The voices we hear are symbolic of the voice of God she hears. Later, while burning on the stake, Joan speaks to God, accompanied by dramatic vocalization, again with the two-note chord sounding as she cries out, “Jesus.” An image of a bright light behind clouds appears on the screen with the final musical climax and the end of the movie.

(Nauman 2009, 244)

Victor Fleming also directed Gone with the Wind (1939) and The Wizard of Oz (1939).

Hugo Friedhofer, orchestrator for Dark Victory (1939) composed scores for The Bishop’s Wife (1947), Joan of Arc (1948), and Boy on a Dolphin (1957), all of which include dramatic vocalization. He contributed to Steiner’s Gone with the Wind (1939), although uncredited, and also was an orchestrator for The Sea Hawk (1940), The Sea Wolf (1941), Kings Row (1942), and The Constant Nymph (1943), all composed by Erich Korngold. In addition, Friedhofer, along with Fred Steiner, helped to complete the final score for The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965).

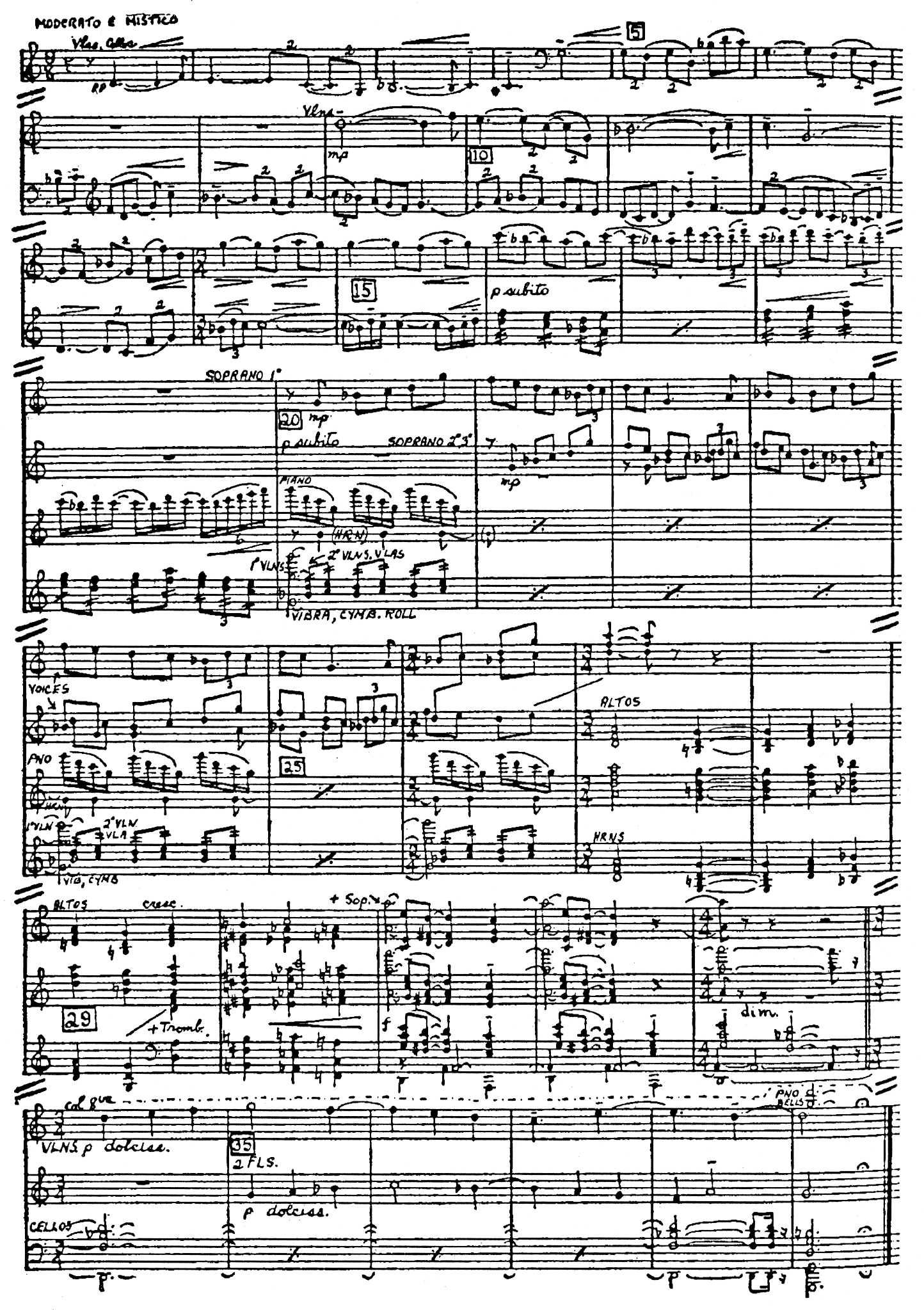

An analysis of the following “The Dauphin Revealed” clip from Roy Prendergast, Film music: A Neglected Art: A Critical Study of Music in Films (New York: New York University Press, 1977), 217–19:

On the basis of screen action, this cue is divided into three sections. The first section covers bars 1–19, the second bars 20–33 and the third section bars 34–39. The sections are not related thematically; each has its own melodic material. The sections are, however, unified by texture, style, and the continuity of the action. This scene takes place at the French court, where, in order to test Joan, it has been arranged to have a courtier pose as the Dauphin. Joan senses the deception, and her “voices” lead her to single out the true Dauphin from the crowd of assembled courtiers.

As any musician will realize, the texture of the music is contrapuntal, for the most part. The opening phrase is answered in bar 9 in canon at the octave. In bar 13 the strict imitation is abandoned in order to begin a brief crescendo. In the next bars, as far as bar 20, the materials are still presented in two-part counterpoint and are almost completely derived from what has come before. This process represents a tiny development with fragments being piled atop each other in a more and more compact fashion. This intensification is increased still further by a rise in pitch and by the sudden change in bar 16 to a relatively homophonic structure. Also, the crescendo does not culminate in the expected climax but, rather, uses the device of a negative accent by going to a subito piano (suddenly soft). The subito piano in bar 20 begins the second section, which is a canon in three parts at the unison for treble voices. These voices in the score represent Joan’s “voices.” The orchestral accompaniment at this point should be regarded as no more than coloristic accompaniment, secondary to the vocal parts. Now ensues the delayed climactic passage, with the alto voices, horns, and trombones swelling into rich harmonies. This climax is placed approximately in the third quarter of the piece, which, while serving the dramatic needs of the picture, also proves advantageous to the symmetry of the music. The remainder of this cue, from bar 34 on, is a musical and dramatic tapering off from the climax; it ends with a quiet theme in canon at the fifth below.

Of incidental interest is the fact that this cue uses the Dorian mode on G and that it employs a characteristic contrapuntal element of sixteenth-century counterpoint in that the melody never leaps a greater interval than a minor sixth. The range of the melody, however, does go beyond the restricted range of the ninth. The harmonies are also unobtrusive since there is nothing more complex than a triad. The progression of triads in the climactic section are definitely “contemporary” but the listener still perceives the section as predominantly modal in character. This particular sequence, while not the most complex in the score, is one of the most effective.

Examples | Comments |

| The Dauphin Revealed [0:34:50–0:35:26] Joan magically picks the real Dauphin out of the crowd. | ||

| Joan’s Prayer [0:57:05–0:57:22] Joan prays to God before the first battle of the movie. | ||

| Joan’s Revelation [2:12:45–2:14:06] Joan’s revelation in prison before her execution. Chorus as “voice of God.” | ||

| Joan at the Stake [2:24:38–2:25:40] Joan burning on the stake. [Transformative vocalization—shining light of God, etc.] |