Dramatic Vocalise Database

Stothart, Herbert (1885–1949)

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

Unlike Gone with the Wind and Dark Victory, The Wizard of Oz was part of the Hollywood film-musical tradition. In Oz there are obvious, diegetic musical numbers such as “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” and “Ding Dong, the Witch Is Dead,” and also passages of non-diegetic background music. Two of the latter passages include dramatic vocalization.

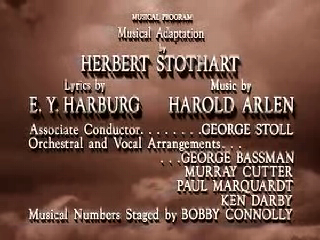

The music for the opening credits of The Wizard of Oz, a medley of tunes from the film, functions like a typical musical overture. After a few measures of introductory material, the brass instruments play the opening melody from “Ding Dong, the Witch Is Dead,” followed by a wordless vocal swell accompanying the screen displaying “Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Presents.” “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” then takes melodic prominence, followed by an upbeat transitional section. Halfway through the “overture,” the mood shifts radically to one of somber melancholy, accompanied by wordless vocalization, for the “Musical Program.”

The Wizard of Oz, “Musical Program” 1

The disembodied chorus, singing “ooh,” gives the moment a particular, if ambiguous significance. The voices exit at the end of this “program.” The full orchestra sans voix majestically presents the continuation of the melodic idea for the remainder of the credits.2

The second instance of dramatic vocalization in Oz occurs as Dorothy (Judy Garland) steps from the sepia-tone world of Kansas (striking for its evocation of the drabness of the Depression and Dust Bowl era) and enters the land of Technicolor. The wordless chorus sounds as signifier of the supernatural realm she has stepped into.

Beginning with silence, Dorothy opens the door of her Kansas home; the music begins. It is harmonically unclear at first, complementing Dorothy’s bewildered look. Then, as she smiles, the music finds stability in an instrumental rendition of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” Wordless chorus enters as the camera pans her surroundings, showing the audience Dorothy’s perspective. The oboe sounds a warning, followed by a wordless solo soprano melody, announcing the arrival of Glenda, the Good Witch. “Ding Dong, the Witch Is Dead” then follows. Dorothy exclaims, “Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore,” followed by wordless chorus singing the melody of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” This provides a narrative description of the particular location which Dorothy then reaffirms: “We must be over the rainbow!”

It is unclear who was responsible for the musical sections containing dramatic vocalization. An examination of the “Musical Program,” however, presents some evidence.

Harold Arlen (1905–86), born Hyman Arluck, was a songwriter who had previously worked with Ted Koehler as lyricist, and in the early Thirties was the staff composer for Harlem’s Cotton Club, a premiere showcase for African-American entertainers such as Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, and Ethel Waters. In the following years he wrote primarily for Broadway and Hollywood. According to Aljean Harmetz, “When the score [of The Wizard of Oz] was finished, Arlen sat down at a piano in a small room at MGM and played his way through his songs, accompanying himself by singing the lyrics. Herbert Stothart listened. The score was now his baby.” 3 The implication in this last statement is that Arlen only wrote the “songs” for Oz, but not the background music or the orchestrations. Stothart probably composed these, with help from George Stoll, George Bassman, and Robert Stringer.4

(Nauman 209, 239–41)

Examples | Comments |

| Opening Credits [0:00:10–0:00:13] Wordless vocal swell for “Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Presents” [0:00:46–0:00:60] “Musical Program” | ||

| Transition to Oz Dorothy steps from the sepia-tone world of Kansas into Oz, i.e., the world of Technicolor. |

Footnotes

1 “Main Title,” Disc 1, The Wizard of Oz, special ed. DVD, directed by Victor Fleming (1939; Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video, 2005).

2 Many other films use wordless vocalization in their opening credits to foreshadow the “surprise” yet to come. See The Ox-Bow Incident (1942), The Robe (1953), The Abyss (1989), and Mars Attacks! (1996).

3 Aljean Harmetz, The Making of The Wizard of Oz (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977), 89.

4 Ibid., 92. Max Steiner and Erich Korngold, both at Warner Brothers, and Alfred Newman at Fox were considered the best of the screen composers. Steiner won three Academy Awards; Korngold, one; and Newman, nine. Stothart’s only award was for The Wizard of Oz.