Dramatic Vocalise Database

Béla Bartók (1881–1945)

The Miraculous Mandarin, Op. 19 (1918–19, orchd 1924, rev. 1926–31)

Béla Bartók (1881–1945) spent August and September 1905 in Paris, where he participated in the Rubinstein competition both as composer and pianist. He returned to Paris in 1910 to perform several of his own works at a “Hungarian festival” concert on 12 March 1910. According to Malcolm Gillies, in Bartók’s works of 1910–12 French influences are at their most apparent, with Debussy’s influence in particular being perhaps too readily noticeable. Gillies cites as examples the Two Pictures, op. 10 (1910) for orchestra, the opera Bluebeard’s Castle (1911), and the Four Orchestral Pieces, op. 12 (1912).1

Contradicting Gillies’ opinion is an essay from 1911 written by Bartók regarding the Viennese premiere of Delius’s Messe des Lebens, in which Bartók claims that it was Delius who used chorus without text for the first time, which suggests that he was not acquainted with Debussy’s Nocturnes.

Delius is the first composer to use—with full self-consciousness—the chorus without text as a color element in the orchestra. . . . And it is noteworthy that apart from the three profound last numbers of the Mass, which are perfect from every point of view, it is just these choruses that make the greatest and most vivid impression throughout the entire work: in the sense as if the choice of the new means would have had an influence on the novelty of ideas and content.

The adoption of the human voice—divested of the word—as an instrument is still the first attempt only in this Mass. But after hearing this attempt we can visualize, so to speak, what enrichment in terms of new colors and entirely new effects the further development of this technical device means.2

Bartók continues:

We can only marvel that such use of the human voice has not occurred to anyone prior to this time. Today, however, three composers simultaneously have the intention of solving similar problems! Because Delius is not the only one with this idea. In Hungary, Zoltán Kodály—without even knowing Delius by name—has been engaged along the same lines, which he partly materialized with a folk song from Nyitra County adapted for women’s chorus (the chorus, without text, accompanies the soli singing of the folk song). And hardly had a few people taken notice of that, when the news came from Paris that in 1910, at the first concert of the S.I.M. [Société Musicale Indépendante], a septet by André Caplet was presented for three women’s voices and four string instruments.3

Bartók was willing to credit Delius, his fellow countryman Kodály, the French composer André Caplet, and yet not Debussy. Interestingly, however, the following passage from the same essay is similar to a passage in one of Debussy’s own letters.

Bartók:

There is no question that one can more easily accustom oneself to a textless chorus which is—so to speak—less “queer”; one can easily conceive of the mass of singers as a patch of color amidst the orchestra. These two kinds of groups amalgamate as readily as the solo voice with several strings.4

Debussy:

I ought also to give you some particulars about Printemps. It’s not really a choral work (the chorus part is wordless and more like an orchestral group). It’s a symphonic suite with chorus. So the interest lies mostly with the orchestra, and one of the difficulties of the chorus parts is the way they and the orchestra blend in together. The whole thing’s a matter of ensemble and the mingling of the colors; both need a light touch.5

Whether inspired by Debussy or Delius, Bartók included dramatic vocalization in his pantomime A csodálatos mandarin (The Miraculous Mandarin), op. 19. He drafted the work in short score to a scenario by Menyhért Lengyel between October 1918 and May 1919, orchestrating it five years later. The work was finally given its first performance in Cologne in 1926, but was banned immediately on moral grounds and not staged again during Bartók’s lifetime. Although an orchestral suite consisting of almost the first two-thirds of the work quickly found a place in the orchestral repertoire, full stagings have remained infrequent.

The problem was the supposedly sordid subject matter of Lengyl’s scenario: three ruffians force a young girl to lure men to her apartment with a view to robbing them. The third victim is a wealthy Chinese Mandarin who remains ice-cold and impassive until the girl’s dancing awakes his frenzied and destructive desire. As the girl shrinks from him in terror, the men try to kill him without success. In the end he dies only when the girl shows him pity.

It is during the last of the threefold attempts to kill the Mandarin—mirroring the three encounters with the potential victims—that Bartók includes hidden wordless chorus (SATB). When the ruffians attempt to hang the Mandarin from a light cord:

The hanging body of the mandarin begins to glow with a bluish green light—his eyes are firmly fixed on the girl.6

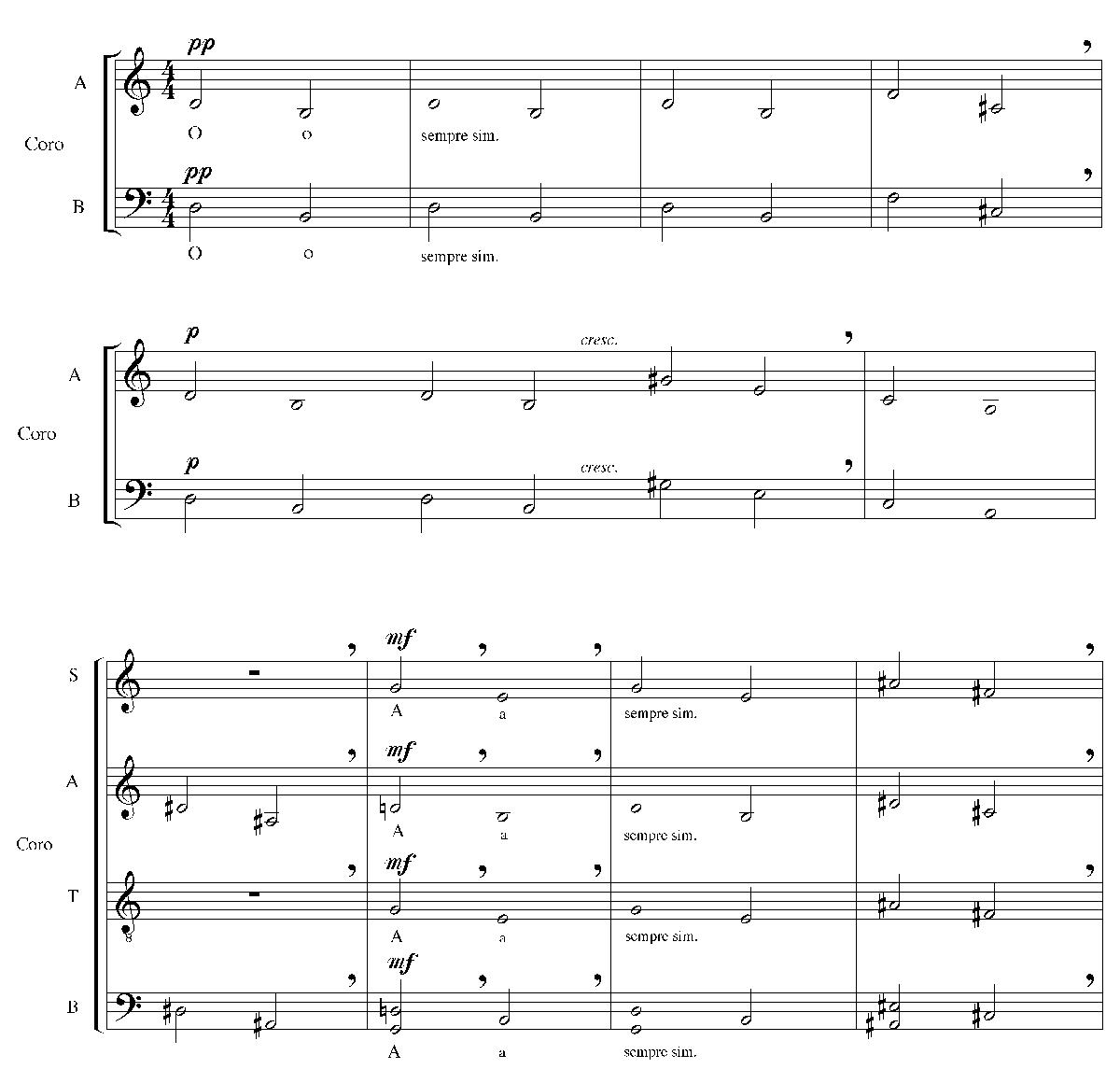

At this moment the chorus enters singing the vowel “O” for nine measures, then an additional ten measures on the vowel “A” (see Example).

Bartók, A csodálatos mandarin

According to Ferenc Bónis, “The minor third motif, sung by an invisible choir, wailing and without words, erupts from the depth of his soul as an expression of infinite suffering and a desire impossible to quell.” 7 This short passage, and the only one in the pantomime that includes chorus, is intended to enhance the impact of this supernatural occurrence, to magnify its otherworldly effect.

(Nauman 2009, 215–20)

Examples | Comments |

| (excerpt) |

Footnotes

1 Malcolm Gillies, “Bartók, Béla,” in Grove Music Online, ed. Laura Macy, http://www .grovemusic.com (accessed 3 January 2007).

2 Béla Bartók, Essays, ed. Benjamin Suchoff (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1976), 449–50.

3 Ibid., 450.

4 Ibid.

5 François Lesure and Roger Nichols, eds., Debussy Letters, trans. by Roger Nichols (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987), 24.

6 Béla Bartók, Der Wunderbare Mandarin, op. 19 (Vienna and London: Universal Edition, 2000), 182.

7 Ferenc Bónis, “‘The Miraculous Mandarin’: The Birth and Vicissitudes of a Masterpiece,” in The Stage Works of Béla Bartók (London: John Calder; New York: Riverrun, 1991), 93.