Dramatic Vocalise Database

Charles Ives (1874–1954)

Symphony No. 4 (ca. 1912–18; ca. 1921–25)

American composer Charles Ives included a “Distant Chorus” in the fourth and final movement of his Symphony no. 4 (1909–1916). Although the first two movements were played in 1927 and the Fugue in 1933, the complete work was not performed until 26 April 1965 by the American Symphony Orchestra at Carnegie Hall, conducted by Leopold Stokowski.

In an autobiographical memorandum from 1932, Ives stated the following:

The last movement (which seems to me the best, compared with the other movements, or for that matter with any other thing that I’ve done) was finished in the summer of 1915 [changed to 1914].1

Scholars and critics alike have echoed this sentiment, although none specifically discusses the novelty of the wordless chorus. According to Wilfrid Mellers:

This movement is probably—with The Housatonic at Stockbridge—the most profound and the most completely realized music Ives ever composed; the final dissolution into silence is a visionary moment of extraordinary poignancy.2

In his review of the work, Kurt Stone similarly writes:

The fourth movement has a quality of portentousness rarely if ever encountered in Ives’s music. It is more haunting, generates a deeper emotional communication than perhaps any other work of his. All the awkward, extraneous characteristics of Ives the odd-ball experimenter are absent, as are his rather frequent lapses of taste, musical and otherwise. This movement seems to me to be one of the most remarkable, most profoundly moving pieces of music ever written by an American composer.3

And Eric Salzman joins the chorus of praise in his notes for a 1976 recording of the work with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Seiji Ozawa:

Perhaps no single work sums up the Ivesian vision better than the Fourth Symphony. It is his most ambitious composition, both in scoring and in its multiple layers. . . . The last movement, one of the most original and powerful Ives ever wrote, takes up earlier motifs, sets them over a percussion ostinato and builds up to a tremendous climax (with voices) before dying away.4

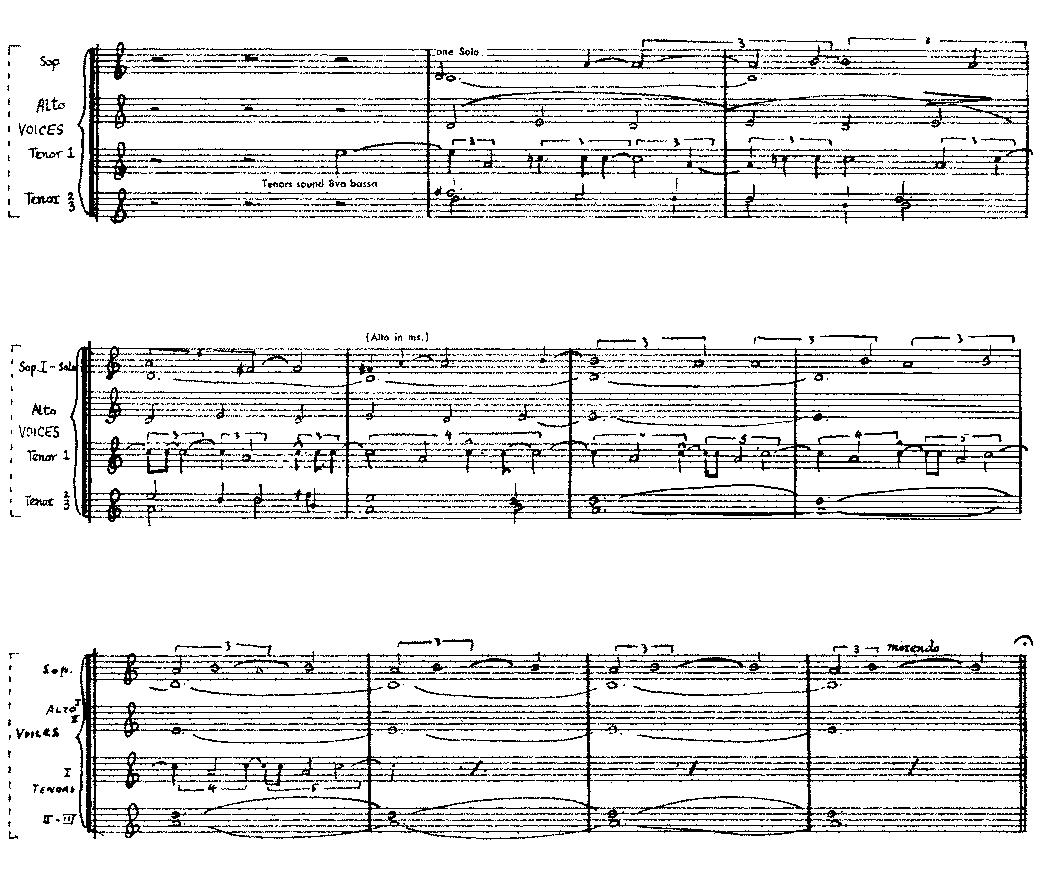

At the end of the last movement the distant, wordless chorus sings the first phrase (mm. 9–11) from the second half of Lowell Mason’s hymn Bethany (“Nearer, my God to Thee”).

Mason, Bethany (“Nearer, my God to Thee”)

Ives does not provide a vowel indication in his score for this wordless rendition. After the prolonged last note of the hymn, the background gradually recedes into the distance as one instrument of the orchestra after another falls silent.

Ives, Symphony no. 4, mvt. 4, mm. 78–88

5In commentary to a 1929 printing of the second movement in the publication New Music, Ives provides a clue as to the meaning of the chorus:

The last movement is an apotheosis of the preceding content, in terms that have something to do with the reality of existence and its religious experience.6

Whatever the personal meaning for Ives, this example shares characteristics with several other pieces included in this database. The chorus is wordless, and the hymn tune symbolizes Ives’s transcendentalist philosophy, much as Holst’s and Vaughan Williams’s compositions relied on dramatic vocalization to symbolize theosophy and mysticism respectively.

(Nauman 2009, 212–15)

Examples | Comments |

| mvt. 4, mm. 78–88 |

Footnotes

1 Quoted in John Kirkpatrick, preface to Symphony no. 4, by Charles Ives (New York: Associated Music Publishers, 1965), viii.

2 Wilfrid Mellers, review of Symphony no. 4, by Charles Ives, American Symphony Orchestra, Leopold Stokowski, Musical Times 107 (1966): 610.

3 Kurt Stone, “Ives’s Fourth Symphony: A Review,” Musical Quarterly 52 (1966): 11.

4 Eric Salzman, liner notes to Symphony no. 4, by Charles Ives, Deutsche Grammophon DG 423 243-2, 2–3.

5 Charles Ives, Symphony no. 4 (New York: Associated Music Publishers, 1965), 177, 179, 181.

6 Quoted in John Kirkpatrick, preface to Symphony no. 4, by Charles Ives, viii.