Dramatic Vocalise Database

Othmar Schoeck (1886–1957)

Lebendig begraben, Op. 40 (1926)

Schoeck’s Lebendig begraben [Buried Alive], op. 40 (1926), proves to be an important piece in the history of dramatic vocalization, since it represents one of the first orchestral song cycles to include an offstage wordless chorus. According to Hans Corrodi, the work is:

a cycle of fourteen songs with orchestra on poems by Gottfried Keller, [which are] the lament and the agonized cry of one buried alive under a mountain of civilization’s rubble, one whose voice can no longer reach the ear of any human creature, since none can hear the pleading of his own heart in the din of the idolatrous dance.1

Later in the same article Corrodi describes the work in further terms:

“Lebendig begraben” (1926) is one of Schoeck’s great personal confessions, in which he draws his conclusions about a world given up to ugly materialism, which, in the midst of the uproar of machinery, financial collapse and intellectual anarchy, drives straight on to a second world war. The work oscillates between the poles of a grandiose power of emotional expression and a graphic representation of the situation of one who is buried alive that may almost be said to trouble one’s optic nerve. Implacable realism in the description of horror, sumptuous richness of color in the painting of the landscape visions and inspired greatness of lyrical pathos—these are the distinctions of this poem for voice and orchestra. Schoeck here expanded the bounds of lyricism: he drew upon the glowingly expressive vocal line of his tragic opera “Venus” (1922) as well as on the piled-up chords of the music-drama “Penthesilea” (1924–25), where he had used a daring harmonic idiom producing stress between chordal complexes of unrelated keys heard in a kind of tonal perspective.2

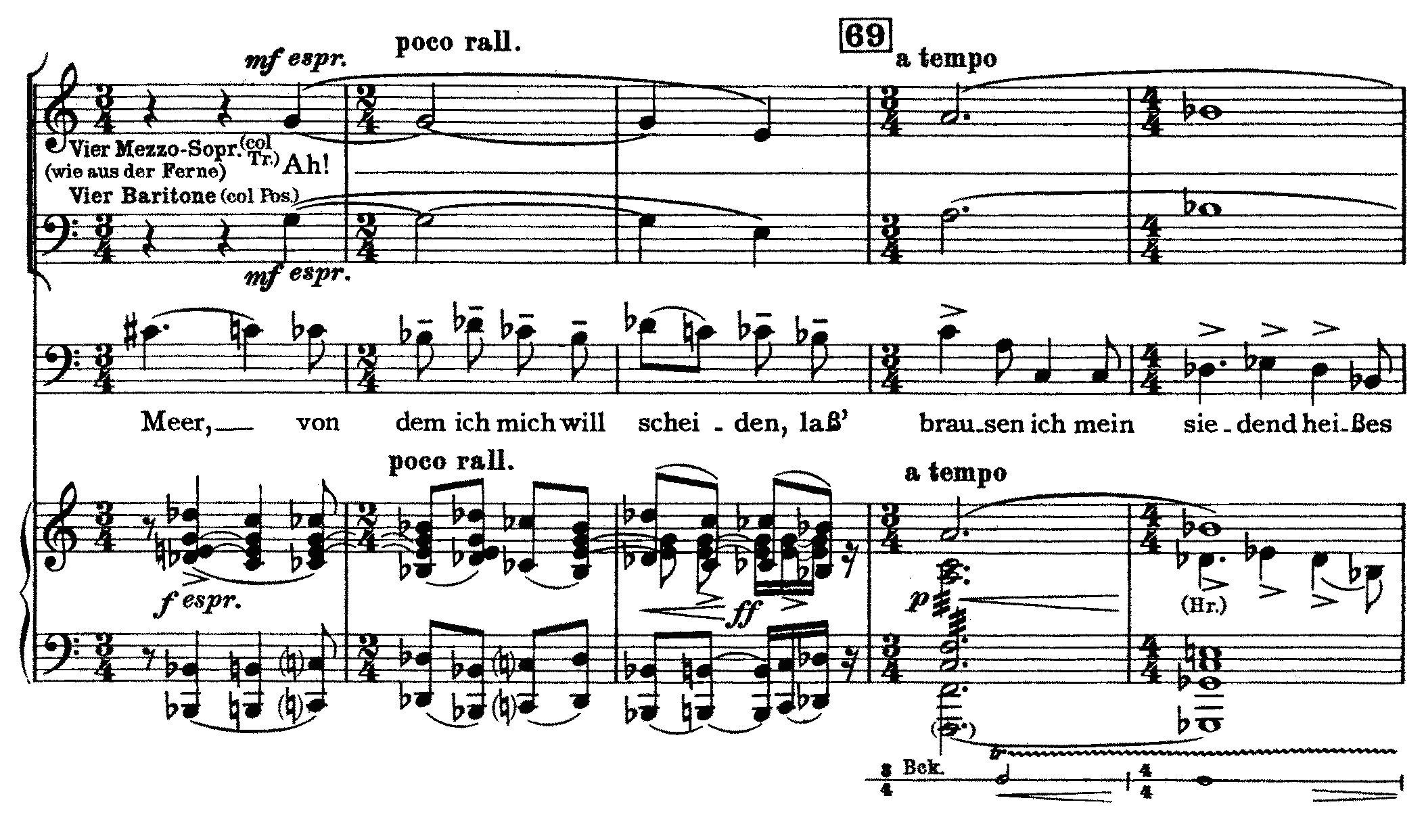

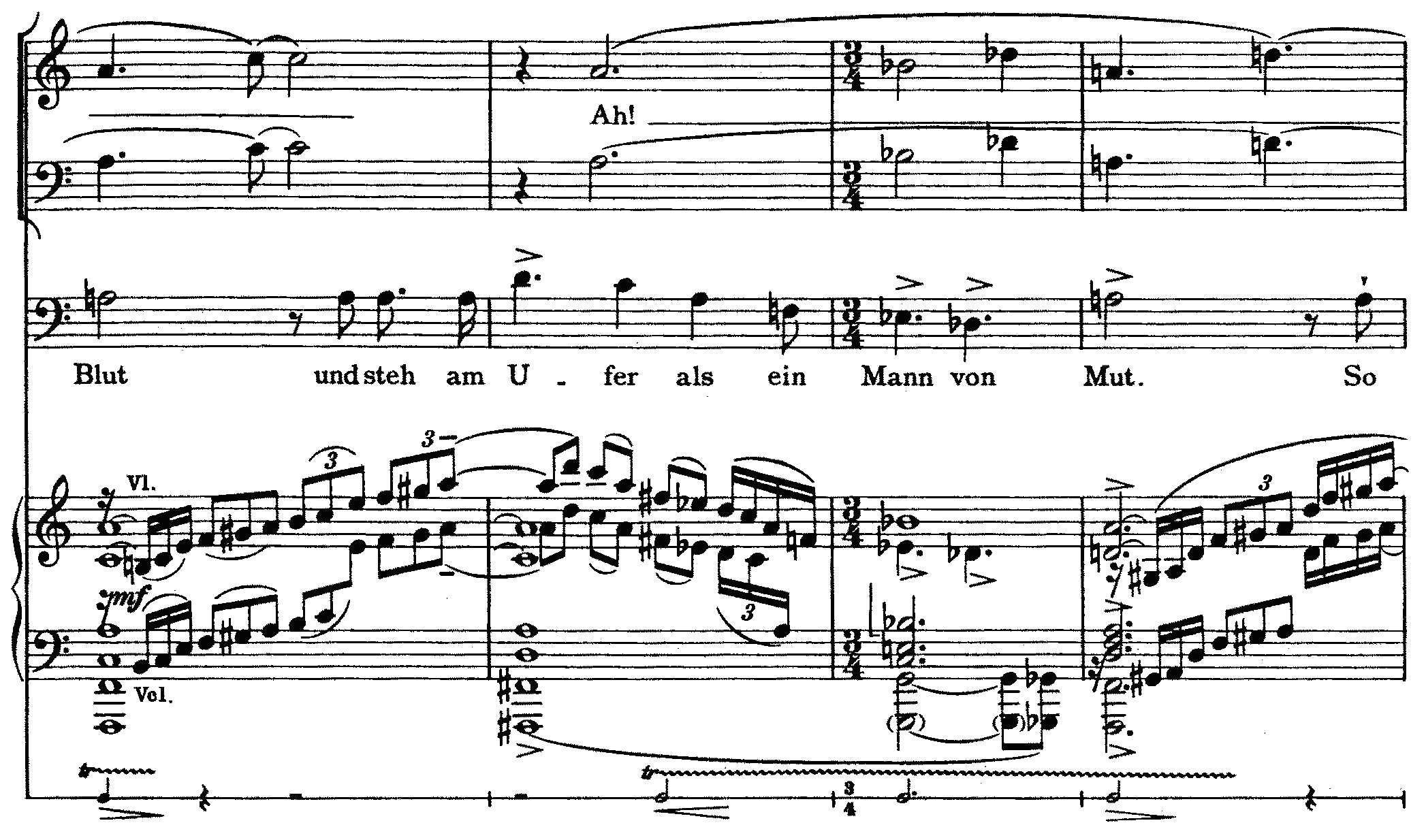

The fourteenth, and last, song includes wordless vocalization—four sopranos and four baritones indicated in the score as “wie aus der Ferne” [“as if from the distance”], singing in octaves, and doubled by trumpets and trombones respectively—as the narrator begins to sing his final farewell.

Schoeck, Lebendig begraben, mm. 822–30

3In an article of 2001, Robin Holloway describes this ending as evoking “ecstatic abandonment—freedom at last—into a pantheistic compound of ocean, sky, eros, and Helvetia” and describes the inspired moment of the score as “among the great well-kept secrets of 20th-century music.” 4

(Nauman 2009, 225–26)

Examples | Comments |

| No. 14, mm. 819–62 |

Footnotes

1 Hans Corrodi, “Othmar Schoeck’s Songs,” Music & Letters 29 (1948): 130.

2 Ibid., 134.

3 Othmar Schoeck, Lebendig begraben (Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1956), 72–73.

4 Robin Holloway, “Schoeck the Evolutionary,” Tempo 218 (2001): 3.